|

"It

seems to me," said Booker T., Dudley Randell, "Booker T. and W. E. B.," 1952. |

The

historical development of Black people's educational experiences reflects

the operation of economic, political, and social forces of the capitalist

society in the United States. The level of social and economic development

of a society sets standards for the skills people must obtain in order to

lead productive lives and contribute to the maintenance of that society. In

class society, the main factor determining who obtains a given skill-level

is the political factor of who rules. The level of technological

development and resulting division of labor are important factors and grow

in importance over the long-run.

It is popularly believed that education's main purpose is to benefit the masses of people by training them for jobs and facilitating upward mobility. Our analysis, however, reveals that the primary function of education in the United States is to serve the interests of the ruling class through achieving two main objectives: (1) to train a disciplined and skilled labor force which can take its place in the existing order and contribute (mainly its labor power) to the maintenance and expansion of the capitalist system; (2) to indoctrinate the youth of the society in the ideas, beliefs, values, and practices which are also important to maintaining the existing socioeconomic order.

Samuel Bowles, in his study of the educational system, has written:

|

That

educational systems in capitalist societies have been highly unequal

is generally admitted and widely condemned. Yet educational

inequalities are taken as passing phenomena, holdovers from an

earlier, less enlightened era, which are rapidly being eliminated. |

|

Black people have always been the most negatively affected by these inequalities in the educational system.

Control over the educational system is maintained by the ruling class in several ways:

1. The ruling class makes sure that the trustee boards of colleges and universities are "dominated by merchants, manufacturers, capitalists, corporation, officials, bankers," as several studies conclude.

2. The ruling class insures that the ideas which are taught in universities are those which reinforce and do not threaten the existing capitalist social order. This is done through funding only selected projects and through selective hiring and firing (e.g., denying employment and tenure to faculty with radical ideas, as has happened with many activists in the Black liberation movement).

3. The ruling class maintains close ties

between the universities and the government (which it also closely

administers). The government provides billions of dollars for war-related

research and other needed functions and draws heavily on university

faculty for its staff.

For Black people, of course, the twin objectives of education and the operation of the three mechanisms listed above are qualitatively influenced by the history of racist oppression and economic exploitation that Black people have faced. Thus, the educational experiences of Black people must be evaluated in that context.

THE SLAVE PERIOD

Education during the period of slavery was shaped by the main aim of the brutal institution of slavery: to exploit the greatest amount of wealth and profits from the forced labor of slaves. To accomplish this main economic aim, it was necessary to make the slave plantation a self-sufficient unit, capable of producing all or most of its own needs. Thus, under slavery Black people received "on the job training" in many skill areas. In addition to using slaves as field hands and domestic labor, "The masters found it easier and cheaper to have their slaves trained in carpentry, masonry, blacksmithing, and the other mechanical trades," as Sterling Spero and Abram Harris state in The Black Worker. This training can be seen in the quantity and quality of what the slaves produced.

As Booker T Washington observed:

| In most cases if a Southern white man wanted a house built he consulted a Negro mechanic about the plan and about the actual building of the structure. If he wanted a suit of clothes made he went to a Negro tailor, and, for shoes he went to a shoemaker of the same race. In a certain way every slave plantation in the South was an industrial school. |

Despite

the fact that racist scholars would have us believe that slaves were lazy

and incompetent, the woodwork, ironwork, and brick masonry is lasting

testimony to the capacity of slaves to learn, use, and improve on existing

skills.

In addition to "worldly" work-related training, religious instruction was important in the education of slaves, in part because it allowed some people to learn to read. Largely at the urging of missionaries, some slaveholders finally agreed to religious education. They did so for several reasons. First, some "Christian" slave owners felt a "moral" duty to provide religious instruction, if for no other reason than to "humanize" Black people. Second and probably more important, slaveholders quickly learned that religious training often made slaves more hardworking, obedient, and submissive than they would ordinarily be. The most loyal slaves, according to the testimony of many slavemasters, were those who could read the bible. Reading, however, proved to be a double-edged sword, particularly as the years wore on.

Black people themselves also played a major role in providing their own education during slavery. Although slaveowners used a variety of techniques to mold the slaves into loyal, submissive, and efficient workers, slaves were able to develop and transmit a set of beliefs, ideas, values, and practices which were different from what the slaveowners intended. Such themes as the hatred of the slaveowners and their power, the importance of the family, the significance of learning and education, and the value of freedom were among the "illegal" lessons that slaves learned and taught. The main educational mechanisms among slaves were the family, the peer group, the underground church, songs and stories, and the slave community itself.

Opportunities for education also existed for free Blacks in the North. One of the best known schools for Blacks was New York's African Free School, opened by the manumission society in 1787, which served as a model for schools in other northern cities.

Thus, some slaves were "educated" through work-related training, through religious instruction, or through their own efforts. But, regardless of how " they" learned, educated slaves were a dangerous contradiction under slavery. If slaves could read work instructions, they also could read and spread the word about the revolutionary struggles of Toussaint L'Ouverture and the defeat of slavery in Haiti in 1791. Slaves who read passages in the bible about obedience and submissiveness also drew revolutionary implications about the necessity of overthrowing slavery.

In fact, it was the growing struggles of the slaves for freedom - a struggle in which many "educated" slaves and free Blacks were active, participants - that caused slaveowners to rethink the policy of education for Black people during slavery. As the slave revolts increased in the United States after 1820, most southern states passed laws prohibiting the teaching of slaves and preventing them from association with free Blacks. The North Carolina law forbidding any person, whether Black or white, to teach slaves was typical:

|

Whereas the teaching of slaves to read and write, has a tendency to excite dissatisfaction in their minds, and to produce insurrection and rebellion, to the manifest injury of the citizens of this State: Therefore: I. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the State of North Carolina:...That any free person, who shall hereafter teach, or attempt to teach, any slave within the State to read or write, the use of figures excepted, or shall give or sell to such slave or slaves any books or pamphlets, shall be liable to indictment...and upon conviction, shall, at the discretion of the court, if a white man or woman, be fined not less than one hundred dollars, nor more than two hundred dollars, or imprisoned; and if a free person of color, shall be fined, imprisoned, or whipped, at the discretion of the court, not exceeding thirty-nine lashes, nor less than twenty lashes. II. Be it further enacted: That if any slave shall hereafter teach, or attempt to teach, any other slave to read or write, the use of figures excepted, he or she may be carried before any justice of the peace, and on conviction thereof, shall be sentenced to receive thirty-nine lashes on his or her bare back. |

In several states, it even became illegal for parents to teach their own children to read. Note, however, that it was not illegal for slaves to learn "figures," obviously because that skill would help the slaveowners keep track of their, human chattel and property.

In My Bondage and My Freedom, Frederick Douglass summed up the southern mindset that overcame earlier interests in educating Black people:

| "[l]f you give a nigger an inch, he will take an ell;" "he should know nothing but the will of his master, and learn to obey it." "Learning would spoil the best nigger in the world;" "if you teach that nigger - speaking of myself - how to read the bible, there will be no keeping him;" " it would forever unfit him for the duties of a slave;" and "as to himself, learning would do him no good, but probably, a great deal of harm - making him disconsolate and unhappy." "If you learn him how to read, he'll want to know how to write; and, this accomplished, he'll be running away with himself." Such was the tenor of Master Hugh's oracular exposition of the true philosophy of training a human chattel; and it must be confessed that he very clearly comprehended the nature and the requirements of the relation of master and slave. |

Douglass went on to describe how many Black people reacted to this:

"Very well" thought I; "knowledge unfits a child to be a slave." I instinctively assented to the proposition; and from that moment I understood the direct pathway from slavery to freedom... the very determination which he expressed to keep me in ignorance, only rendered me the more resolute in seeking intelligence. |

Throughout the slave period, slaves and free Blacks alike strove to educate themselves.

THE RURAL PERIOD

The defeat of the slaveowners and the southern agricultural system by the rising northern industrial capitalists brought great changes as the tenant system replaced slavery. This new "freedom" of Black people required the development of social institutions that could provide the kind of "social control" that the institution of slavery had provided. Education used as a training ground for leadership became the vehicle of control. Black colleges became, a key mechanism used to train a sector of the Black population in the skills of social control.

|

|

Still, Black people were anxious to be educated. Slaveowners had paid considerable sums to finance the education of their own children and to employ "educated" assistants to help maintain their economic and political power. After slavery, Black people actively sought education as one of the most important tools for liberation. As Booker T. Washington observed, it appeared "a whole race was trying to go to school."

There were four main sources of educational experiences for Black people during the agricultural period:

The Black community - From the beginning of the Civil War, Black people arranged to have lessons offered. Schools were set up with teachers as soon as an area was captured by the Union Army. Almost $1.2 million was contributed in taxes and tuition and by Black church organizations. Black soldiers gave their army pay to help establish schools, such as Lincoln University in Missouri. In South Carolina, the Black-majority state legislature during Reconstruction passed a bill which established the first system of tax-supported public education for all citizens. Many Black people who could already read and write offered invaluable services in establishing schools in the South.

Civic and church organizations - Religious organizations and churches contributed to meeting the educational needs of the ex-slaves. The American Missionary Association opened schools in several areas and later assisted in the founding of several colleges, among them Fisk (1866), Talladega (1867), and Hampton (1868). More than sixty-five societies were organized to support Black education between 1846 and 1867. Between 1862 and 1874, sixteen of these contributed almost $4 million. These organizations also assisted in recruiting teachers and providing school supplies.

Government-sponsored - The government played the major role in orchestrating the development of education for Black people during Reconstruction. From 1866 to 1870, almost half of the $11 million allocated to the U.S. Freedmen's Bureau, created to "assist" the former slaves, went to support Black schools. According to DuBois: "For some years after 1865, the education of the Negro was well nigh monopolized by the Freedmen's Bureau..." Howard University established in 1866 is the best example of a Black college organized by the government. Still, there was a tremendous shortage of funds to finance education. A good deal of the money for financing education ultimately came from northern industrialists.

Northern industrial capitalists - Northern industrial capitalists donated funds to raise the educational and skill levels of people in the South because it was in their interest to do so. During and following the Civil War, northern industrialists established their great monopolies. By the latter part of the 19th century, however, people (especially in the North) began to rise up against this class and its business methods. The capitalists desperately needed to redeem themselves, and the South seemed like a good place to channel their efforts. As, Henry Bullock put it:

| Southern workers were still not strongly organized; industrial peace prevailed in the region, and the growing population offered a good source of cheap labor. With its tax base still impaired, the South became a good outlet for charitable expressions that could possibly repair the image of the industrial class then being shattered by rising class conflict in Northern cities. It presented industrialists with a good opportunity to regain public acceptance while remaining true to their class ideology of rugged individualism. Through charitable contributions to the South's institutional life, they could help the Southern people help themselves, increase labor value where wage scales were kept lower by custom, and open greater consumer markets for the many manufactured products then being created through their industrial leadership. Most attractive of all must have been the appealing recognition that the region's educational leadership had passed to those who identified with the industrial class - to a breed of men who not only spoke the language of this class but also shared its basic aspirations. |

Thus, many of the leading capitalists gave millions of dollars toward education: Slater (cotton textiles), Rockefeller (oil), Pea-body (retail), Carnegie (steel), Morgan (steel and finance), Baldwin (railroads), and Rosenwald (retail, Sears). While their funds were important in increasing educational opportunities, they did much to reinforce the prevailing pattern of racist discrimination against Blacks. For example, they gave Black schools only 2/3 of the allocations given to white schools, they supported racist legislation pertaining to civil rights and education, and their monies upheld segregated educational facilities in the South.

Apart

from these charitable donations, industrial capitalists had other ways of

supporting education for Black children. Their reasons for doing so were

just as self-interested. Horace Mann Bond provides insight into the

company town and its educational policies in his description of the

Tennessee Coal and Iron Company, a subsidiary of U.S. Steel in Westfield,

Alabama.

|

The

Tennessee Company began at once to build up complete industrial and

housing units, fitted with hospitals, welfare centers, and schools,

by which means it was frankly hoped to regularize the uncertain

Negro labor. It was officially stated that this was not a

philanthropic movement: "The Steel Corporation is not an

eleemosynary [charitable] institution," and its first object was

"to make money for its stockholders."... |

Company schools were clearly designed to fill the needs of the particular industry rather than the broader educational needs of Black people.

During the rural period, a significant controversy developed between Booker T Washington and W. E. B. DuBois, particularly over the issue of what educational policy would be most advantageous to Blacks. Washington argued for industrial or vocational education its the major focus. DuBois advocated the education of a "talented tenth" that would provide the broader intellectual leadership and training needed by the masses of Black people.

While the debate centered on education, the two also had different social-political philosophies. Washington's go-slow accommodationist philosophy ("Blacks should not demand full social equality"), in combination with his emphasis on industrial training, was preferred by the industrial capitalists. They were seeking not only to produce more efficient Black workers but to reestablish a good relationship with southern whites. DuBois's militant agitation for full equality and his emphasis on struggle would have continued the conflict between Black and whites and slowed down the economic expansion of northern capital in the South. DuBois's program also would have secured political power for Blacks in some areas of the Black Belt South. Thus, Washington and "the Tuskegee machine" were fully supported by the ruling class (e.g., he was given a private train to use by Carnegie). DuBois, on the other hand, was forced to resign his teaching position at Atlanta University because its funding was threatened as a result of his militant stands.

Historically, racist discrimination has always characterized the education of Blacks in the South. This can be demonstrated by analyzing discrepancies in the allocation of federal, state, and local funds for teachers' salaries, school books, supplies, and buildings. For example, in North Carolina, considered one of the more "enlightened" states, during 1924-25 about $6.7 million was spent on new buildings for rural white children while only $444,000 was spent for Black children. During most of the rural period, Blacks in the North fared little better, particularly when separate (and unequal) public schools were established. Inadequate facilities and diluted academic programs plagued students in Black schools, while vicious discrimination faced those few students who attended mixed schools.

THE URBAN PERIOD

The

migration, industrialization, and urbanization that characterized the

Black experience after World War I had a marked effect on the education of

Blacks. The spread of large-scale machine industry in the South and in the

North ended the Washington-DuBois debate over industrial (handicraft)

training vs. academic training. Neither Washington's nor DuBois's visions

would be realized. Henceforth, at least in higher education, the goal was

to train Black students to become like white bourgeois students who saw

education not in terms of enlightenment but as a means of acquiring money.

Writing about Black colleges in 1957, E. Franklin Frazier observed in Black

Bourgeoisie:

|

Unlike

the missionary teachers, the present teachers have little interest in

"making men," but are concerned primarily with teaching as a

source of The second and third generations of Negro college students are as listless as the children of peasants. The former are interested primarily in the activities of Greek letter societies and "social" life, while the latter are concerned with gaining social acceptance by the former. Both are less concerned with the history or the understanding of the world about them than with their appearance at the next social affair...So teachers and students alike are agreed that money and conspicuous consumption are more, important than knowledge or the enjoyment of books and art and music... Thus it has turned out that Negro higher education has become devoted chiefly to the task of educating the black bourgeoisie. . . . the present generation of Negro college students (who are not the children, but the great grand-children of slaves) do not wish to recall their past. As they ride to school in their automobiles, they prefer to think of the money which they will earn as professional and business men. For they have been taught that money will bring them justice and equality in American life, and they propose to get money. |

For most Blacks, however, the road to higher education, whether in Black or mixed schools, was closed throughout most of the urban period, as it had been in the rural period.

Elementary

and Secondary Education

Apart from the church, the public school was the

main institution that Black families came into contact with in the urban

North. Several problems confronted Black people in the new educational environment. School attendance had

not been mandatory in the South, the curriculum had not been as rigorous

in the South, and most students were underprepared. White teachers and

students reacted negatively to the different cultural backgrounds of

rural, southern Black students. All of this made the situation very

difficult. The concentration and overcrowding of Black people in urban

ghettos and extreme poverty combined with the above difficulties to make

school segregation the prevailing pattern in the urban North. This was

called de facto segregation because it was segregation in fact

based on housing patterns and not segregation by law, or de jure segregation,

as existed in the South.

Numerous protests against school segregation took place. Given the history

of the U.S. government and Supreme Court in legitimating the racist

denial of equal rights to Black people, the

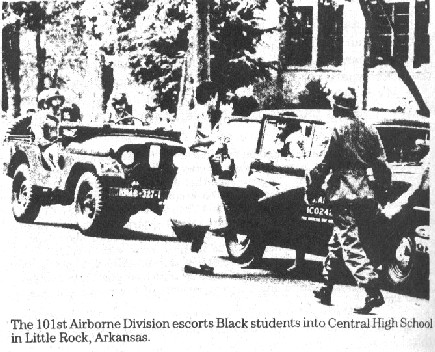

In May 1954, the Supreme Court ruled on cases initiated by Black people and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in four states - Delaware, Kansas, South Carolina, and Virginia - which challenged the denial of admission to public school under state laws permitting racist discrimination.

The NAACP brief argued:

| The substantive question common to all is whether a state can, consistently with the Constitution, exclude children, solely on the ground that they are Negroes from public schools which otherwise they would be qualified to attend. It is the thesis of this brief, submitted on behalf of the excluded children that the answer to the question is in the negative: the Fourteenth Amendment prevents states from according differential treatment to American children on the basis of their color or race. |

The court's decision in the school desegregation cases (called Brown et al. v. Board of Education because those suing were listed in alphabetical order) read: "We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." The Supreme Court, however, dodged the issue of establishing a timetable for desegregation and hid behind the phrase "with all deliberate speed." Howard Moore stated quite baldly what that meant:

| In one of the most humanistic passages in American legal literature, the Court rhapsodized, "To separate them from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status, in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone." Yet, the Courts lacked the mettle to order the immediate remedy of so monstrous an injury...There was absolutely no constitutional warrant for the gradual implementation of the Fourteenth Amendment in the area of public education. It was rank concession to white racism. |

Although there were dramatic changes in the areas of public facilities and accommodations following the Brown decision (largely through the struggle of Black people in the streets), local and state officials have continued to procrastinate. Some twenty-five years after the ruling that "Separate and unequal" facilities should end, over 66% of Black students in the United States are still found in schools that are more than 50% Black and minority.

What makes these schools undesirable is not that they are majority Black, but that they are located in inner-city areas, where most are under funded and without the resources needed to provide the best possible education for Black students. The key to Black education in the cities rests with the economics of inner-city public schools. While an overall budget crisis is affecting all schools, inner-city schools where Black students are concentrated are being hit the hardest. Several tactics have emerged to confront this situation:

Busing - Some Black people support this alternative because the few good schools with sufficient funds are located outside the Black community, and transporting Black students to these schools is seen as one way of providing them access to good education. Most public schools, however, are not providing quality education. This alternative leaves this basic problem untouched and, in fact, does very little for most students. Busing is another example of a government-dictated program, which, like the Bakke decision, inflames racial tensions unnecessarily while not solving the main problem.

Independent educational institutions - These emerged as an alternative to the miseducation of Black students in public school systems. They differ from the private schools initiated by white parents to avoid school desegregation. They include several types: from Montessori schools (which stress developing a child's own initiative in teaching) to the "freedom schools," which have been especially popular among Black nationalists. But these schools must charge tuition. Therefore they do not offer a real alternative for the masses of Black students trapped in poor public schools systems, which their families' tax dollars continue to support.

Community control - Black people have also fought for control over schools and districts which are supported by their taxes. Many of these institutions have a student population that is majority Black, but Black parents, residents, teachers, and administrators have been systematically excluded from decision-making regarding curriculum, teacher hiring and accountability, discipline, etc. Preston Wilcox, a leading Black educator in New York city, has written this about the movement for community control of the public schools:

| The

thrust for control over ghetto schools represents a shift in

emphasis by black and poor people from a concern with replicating

that which is American to a desire

for reshaping it to include their concerns. There is less concern

with social integration than there is with effective education... [B]lacks have begun to recognize that the educational system probably has no intention of educating black Americans to promote their own agendas. The system's preference is for Americans of color to develop pride in white America. What is really feared is collective action by blacks in the economic and political spheres... The thrust, then, for control of schools serving black communities is essentially a surge by black people to have their concerns incorporated into this society's agenda. Any honest examination of the school system will reveal that social class and social caste factors operate to keep black and poor students uneducated.... Two inseparable outcomes will mark the success of this venture: the degree to which black and poor kids invest themselves in the learning process (instead of allowing themselves to be taught that they are slow learners) and the degree to which the local school unit becomes an agent for local community change (not just changing students). |

This alternative, because it focuses on the tax-supported schools where more Black students are, and because it involves the Black community in a collective struggle for power, has the greatest potential for improving the quality of education in the public school system.

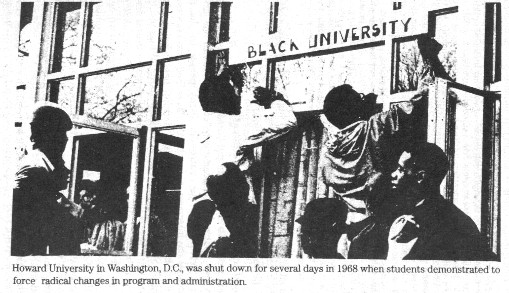

Higher Education

The recent period in higher education for Black people has been shaped by

the militant struggle of the Black liberation movement in the 1960s. This

had two major consequences: an increase in the number of students and an

increase in programs designed to serve needs of Black people. The Black

liberation movement demanded and received a sizable increase in the

enrollment of Black students in higher education and an increase in Black

faculty and staff employment. The dramatic increase in Black college

students reflected the basic change in black community over the last

seventy years. The 1910 census reported that 30.4 % were illiterate , 90%

were living in the South, and 60% of the Black men were employed in agriculture.

In 1916, the office of education reported only 2,132 students at 31

Black colleges. By 1940 though still "over three-fourths of all

Blacks lived in the South, close to two thirds lived in rural areas there,

and just under half were still engaged in agriculture," 34% of Black

people had moved to central cities. These mass-migrations to southern

cities and the industrial North resulted in 58,000 students at 118 Black

colleges by 1940.

By 1969, the U.S. census reported that 55% of Blacks lived in central cities, about 50% lived in the North, and only 4% remained employed in agriculture. Correspondingly, in 1964 there were about 200,000 Black college students, and over triple this ten years later in 1974. This increase in the number of Black college students thus reflects fundamental changes in U.S. society and Black people's situation in it.

Higher education for Blacks can be further understood by describing three specific forms of educational institutions: the private college, the land grant university, and the urban community college. Private schools were set up in the 1850s and 1860s to produce a Black petty-bourgeois elite, particularly in the fields of education, religion, social work, law, medicine, and business. Of all Black college graduates in 1900, 37% were teachers, 11% were ministers, 4% were doctors, 3% were lawyers, and only 1.4% were engaged in farming. This was the "talented tenth" DuBois spoke of While these schools were the only avenue for higher education at one time, they now account for little more than 10% of all Black students.

Another group of schools were set up in the 1890s as a result of the second Morrill Act of Congress. This act set up the land-grant college system to help spread technological innovation and training to aid U.S. agricultural production. This was also the heyday of Booker T. Washington's vocational education philosophy. By 1940, while 22.3% of Black students were still majoring in education, 23% were also majoring in agriculture, industrial arts, and home economics. The situation changed after the World War II. By 1955-56, over two-thirds of graduates from the publicly-controlled Black colleges were graduating with degrees in education. Another change occurred in the late 1960s. Degrees in education fell to 50%, and degrees in the social sciences (social work) rose to 17% and in business to 9% in 1967.

The newest educational institution is the urban community junior college. The community college was created due to advances in skill requirements for the job market. The paraprofessional, clerical, and technical jobs needed more than high-school trained persons. This reflected both the inadequacies of high schools and the special skills needed for jobs. These schools actually began after World War I, but it wasn't until the late 1960s that they boomed. While 18% of all U.S. students are enrolled in community colleges, 32% of Black students are enrolled in them.

The Black liberation movement fueled a militancy among these Black students who were admitted to colleges and universities. It led to the successful struggle of Black Studies, which was to serve as a base for an educational experience relevant to the history and aspirations of Black people for freedom (see Chapter 1).

Because these militant demands were made during the period of the Vietnam War, there were sufficient financial resources for the U.S. ruling class to make these concessions. But the last few years have witnessed a decline in the economic prosperity of U.S. imperialism. One result is belt-tightening in higher education and attempts to cut back or cut out the gains made by Black people during the past ten years. The recent decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in the Bakke case is a most obvious example. Commenting on the Bakke case, Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote:

|

I fear that we have come full circle. After the Civil War our government started several "affirmative action" programs. This Court in the Civil Rights Cases and Plessy v. Ferguson destroyed the movement toward complete equality. For almost a century no action was taken, and this non action was with the tacit approval of the courts. Then we had Brown v. Board of Education and the Civil Rights Acts of Congress, followed by numerous affirmative action programs. Now, we have this Court again stepping in, this time to stop affirmative action programs of the type used by the University of California. |

The impact is becoming clear. There has already been a decline in Black enrollment, not only in medical schools but also in law and other professional schools. Mary Frances Berry sums up the empirical trends as follows:

|

In medical schools between 1969 and 1974 total enrollment increased from 37,690 to 53,354. in 1969 there were 1,042 blacks (2.8%) enrolled, and in 1974, 3,555 (6.3%). In law schools there were 2,128 blacks out of 68,386 in 1969 (3.1%), and 5,304 out of 118,557 in 1978 (4.5%). These numbers are significant because nationally blacks constituted only 1.8% of the lawyers in 1976 and only about 2% of the physicians. After 1974, however, black enrollments in medicine and law and other professional fields declined. First year enrollments in medicine as an example were 7.8% in 1974-75, 6.8% in 1975-76, and 6.7% in 1976-1977. In the Fall of 1982, only 5.8% of medical students were black. Between 1977 and 1978, first year enrollments of blacks in medicine decreased by 1.9% while white enrollments increased 2.5%. In 1976-77, blacks were 5.3% of the first year law enrollments, but by 1977-78 and 1978-79 they were down to 4.9%. In graduate fields other than first professional degrees in 1980 there were 59,929 (5.4%) blacks among, the total 1,096,455 master's and doctoral students, a 3% decline from 1978.These statistics indicate that the enrollment of black students in graduate and professional programs generally increased substantially between 1968 and 1976 with some leveling off and have been declining since 1978. It should also be noted that the gap between blacks and whites in fields of graduate and professional endeavor is still enormous. For example, in the 1980-81 academic year, blacks received only 24 of the 2,551 Ph.D.'s awarded in Engineering and only 32 of 3,140 doctorates in the Physical Sciences. |

The Bakke Case merely legitimated what was already an objective trend in declining Black enrollments in graduate and professional programs.

Thus, Black people in the 1980s clearly understand that educational opportunities, though fought for and won, have not been the keys to liberation that many once believed. Education for Black people still reflects the oppression that Black people suffer at the hands of the dominant economic and political forces in this society. It is important, therefore, that we escalate the struggles against attacks on affirmative action and the fight for community control of schools, Black Studies, and other educational activities that seek to contribute to the liberation of Black people.

KEY CONCEPTS

| Affirmative action | Community control | |

| Bakke Decision | De jure vs. de facto school segregation | |

| Black educational institutions | Liberal arts education | |

| Brown decision | Literacy |

|

| Busing | Vocational education |

STUDY

QUESTIONS

1.

What educational experiences have characterized the three periods of Afro-American

history?

2. What kinds of struggles have Black people waged for greater educational opportunities and what impact have they had?

3. Does education result in upward social mobility? If yes, why? If no, why not?

4. What produces academic excellence in Black students?SUPPLEMENTARY READINGS

1.

Horace Mann Bond, Negro Education in Alabama: A Study in Cotton and

Steel. Washington, D.C.: Associated Publishers, 1939.

2. W.E.B. DuBois, The Education of Black People: Ten Critiques, 1906-1960. Edited by Herbert Aptheker. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1973.

3. Geneva Smitherman, Talkin'and Testifyin'. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1977.

4. Thomas L. Webber, Deep Like the Rivers: Education in the Slave Quarter Community, 1831-1865. New York: W. W. Norton, 1978.

5. Meyer Weinberg, A Chance to Learn: A History of Race and Education in the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977.