|

Since

her arrival on these alien shores, the black woman has been subjected

to the worst kinds of exploitation and oppression. As a black, she has

had to endure all the horrors of slavery and living in a racist

society; as a worker, she has been the object of continual

exploitation, occupying the lowest place on the wage scale and

restricted to the most demeaning and uncreative jobs; as a woman ,she

has seen her physical image defamed and been the object of the white

master's uncontrollable lust and subjected to all the ideals of white

womanhood as a model to which she should aspire; as a mother, she has

seen her children torn from her breast and sold into slavery, she has

seen them left at home without attention while she attended to the

needs of the offspring of the ruling class. Frances Beal, "Slave of a Slave No More," 1975.

|

|

The particular problems and concerns of Black women must be discussed not as isolated questions, but as a part of the problems faced by all Black people. Over 52% of all Black people in the United States are women. Women play a special role in bearing children and in the family, and increasingly are becoming sole heads of households. However, Black women face greater discrimination than any other group in this society - in income, in job opportunities, in education, in holding political office, and in other areas of social life.

The oppression of Black women has its historical roots in the foundation and development of capitalism and imperialism in the United States. This special oppression is based on three things:

1. Most Black women are workers and are subjected to economic (class) exploitation at the hands of the rich. Black women have always worked and this more than anything else has shaped the experience of Black women in the United States. In fact, the work experiences of Black women make their concerns somewhat different from those of the women's liberation movement which seeks to get white women into the work place. Both Black and white women, however, share the demand of equal pay for equal work.

2. Black women, as do the masses of Black men, suffer from many forms of racist national oppression, like job discrimination and the denial of basic democratic rights.

3. Black women, like all women, face male supremacy (sexism) which attempts to put women into subordinate roles in a male-dominated society. This is reflected in the role of women in the Black family. In short, the oppression of Black women grows out of the same system of capitalism that exploits and oppresses the masses of Black people and everybody else, and it is buttressed by patriarchal ideology. The particular content of this oppression has been transformed as the experiences of Black people have changed from slavery to the rural experience to the urban experience. These three periods provide the historical framework for our analysis of Black women and the family.

THE SLAVE PERIOD

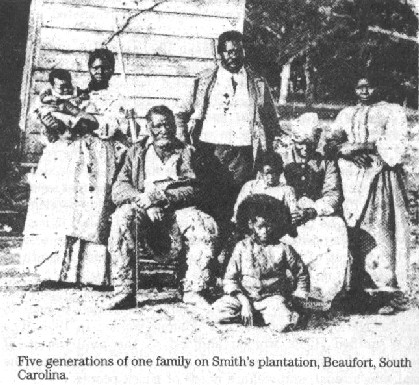

There was full employment for Black people during slavery. It is estimated that half of the slaves in the United States in 1860 were women. Their labor was exploited in three main sectors of the economy: in the fields, in the household, and in industry.

As field slaves, women's main activity (like men's) was to produce crops (first tobacco and sugar and later cotton), which were pivotal to the early development of the United States. As house slaves, women (more so than men) were used as domestic servants, keeping the slaveowners' houses, cooking their food, and raising their children. Women were also exploited in many industries in the South. Robert Starobin reported in his 1970 study of industrial slavery:

| Slave women and children

comprised large proportions of the work forces in

most slave-employing textile, hemp, and tobacco factories. Florida's

Arcadia Manufacturing Company was but one example of a textile mill

run entirely by 35 bondswornen, ranging in age from fifteen to

twenty years, and by 6 or 7 young slave males. Young slaves also

operated many Kentucky and Missouri hemp factories...Slave women and

children also worked at "light" tasks in most tobacco

factories; one prominent tobacco manufacturer, who employed twenty

slave women "stemmers," six boys, and a few girls, used

for the arduous task of "pressing" the tobacco only ten

mature slave males in the entire factory. Slave women and children sometimes worked at "heavy" industries such as sugar refining and rice milling...During the height of the rice milling season, one large steam rice mill added fifty bondswomen to the normal work force of forty-eight bondsmen, while another steam rice mill supplemented twelve slave men with ten boys and girls. Other heavy industries such as transportation and lumbering used slave women and children to a considerable extent. In 1800, slave women composed one-half of the work force at South Carolina's Santee Canal. Later, women often helped build Louisiana levees. Many lower South railroads owned female slaves, who worked alongside the male slaves. Two slave women, Maria and Amelia, corded wood at Governor John A. Quitman's Mississippi wood yard. The Gulf Coast lumber industry employed thousands of bonds- women. Iron works and mines also directed slave women and children to lug trams and to push lumps of ore into crushers and furnace. |

In the view of many factory owners, women cost less to maintain. Because they could work faster in certain jobs, they also produced more than men in industries like textiles. For women who were field slaves and industrial slaves, long hours of housework (cooking, sewing, etc.) were usually added to a full day of production work.

The necessity of (forced) work left little time to raise a family. However, stable family relations did develop among slaves, though these were always subject to the economical and political dictates of the slave system. The common plight of oppression and exploitation suffered by slave men and slave women created a concrete basis for equality, as well as developing strong and independent Black women. Some slaveowners respected the mother/father/child relationship because this often increased the slave family's economic efficiency (and discouraged rebellious male slaves from running away).

Many, however, broke up families in order to profit from the sale of slaves. Solomon Northup, a slave himself, described a familiar scene during the slave period:

|

The

same man also purchased Randall. The little fellow was made to jump,

and run across the floor, and perform many other feats, exhibiting

his activity and condition. All the time the trade was going on,

Eliza was crying aloud, and wringing her hands. She besought the man

not to buy him, unless he also bought herself and Emily. She

promised, in that case, to be the most faithful slave that ever

lived. The man answered that he could not afford it, and then Eliza

burst into a paroxysm of grief, weeping plaintively. Freeman [owner

of the slave-pen] turned round to her, savagely, with his whip in

his uplifted hand, ordering her to stop her noise, or he would flog

her... She

kept on begging and beseeching them, most piteously, not to separate

the three. Over and over again she told them how she loved her boy.

A great many times she repeated her former promises - how very

faithful and obedient she would be; how hard she would labor day and

night, to the last moment of her life; if he would only buy them all

together. But it was of no avail; the man could not afford it. The

bargain was agreed upon, and Randall must go alone.Then Eliza ran to

him; embraced him passionately; kissed him again and again; told him

to remember her - all the while her tears falling in the boy's face

like rain. Freeman damned her, calling her a blubbering, bawling wench, and ordered her to go to her place, and behave herself, and be somebody. He swore he wouldn't stand such stuff but a little longer. He would soon give her something to cry about, if she was not mighty careful... |

Despite

these difficulties, the slave family played an essential role. As John

Blassingame concluded in The Slave Community, the slave family

"was primarily responsible for the slave's ability to survive on the

plantation without becoming totally dependent on and submissive to his

master."

In

The Negro Family in America, E. Franklin Frazier described the

special role of the mother in the slave family:

| Among the vast majority of slaves, the Negro mother remained the most stable and dependable element during the entire period of slavery...Most of the evidence indicates that the slave mother was devoted to her children and made tremendous sacrifices for their welfare. She was generally the recognized head of the family group. She was the mistress of the cabin, to which the "husband" or father often made only weekly visits. Under such circumstances a maternal family group took form and the tradition of the Negro woman's responsibility for her family took root. |

Two main forms of oppression based on sex were suffered by slave women. First, female slaves were subjected to the grossest sexual abuse. According to Frederick Douglass, "the slave woman is at the mercy of the fathers, sons, or brothers of her master," not to mention the slaveowners themselves. Rape and unwanted pregnancies became the common plight for slave women. Forcing Black women to become "breeders" to reproduce the supply of slave labor, especially after the end of the slave trade, was the most extreme form of this sexist oppression. Second, Black female slaves who were forced to work in production could spend very little time with their families. As a house slave, many a slave woman was forced to become a "mammy" to the children of her oppressors while her own children were neglected.

Black women were actively engaged in the struggle to overturn slavery. There were individual struggles, like those recounted by an ex-slave whose mother provided a model for her struggle out of slavery:

|

Ma

fussed, fought and kicked all the time. I tell you, she was a demon.

She said

that she wouldn't be whipped, and when she fussed, all Eden must

have known it. She was loud and boisterous, and it seemed to me that

you could hear her a mile away...With all her ability for work, she

did not make a good slave. She was too high-spirited and independent.

I tell you, she was a captain. |

There were also collective efforts, like those of Harriet Tubman. She was called the "Black Moses" because of her role as a leader in the underground railroad, a secret escape route to the North used by many slaves. Free Black women like Frances Ellen Watkins Harper were active in the abolitionist movement in the North, traveling and speaking to mobilize support for the struggle against slavery. Thousands of other Black women, whose contributions have yet to be recorded, undoubtedly played active roles in this struggle.

Black

women were also active in the struggle against the special oppression of

women. Many white women were inspired by the fight against slavery. The

struggle against slavery and the women's rights movement had a common

enemy. The same arguments regarding the human rights of slaves were applied

by women in the struggle against their own oppression, especially as they demanded the right to vote and full equality in politics, education,

employment, and marriage. Black

women who were militant anti-slavery activists played active roles in the

women's movement.

Sojourner Truth articulated the thoughts of many Black women:

|

|

Indeed,

Sojourner Truth continued to speak out on women's rights. In 1867 as Black

men were gaining their civil rights, she declared:

|

There

is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word

about the colored women; and if colored men get their rights, and not

colored women theirs, you see the colored men will be masters over the

women, and it will be just as bad as it was before. So I am for keeping

the thing going while things are stirring; because if we wait till it is

still, it will take a great while to get it going again...I want women

to have their rights. In the courts women have no right, no voice; nobody

speaks for them. I wish woman to have her voice there among the

pettifoggers... I have done a great deal of work; as much as a man, but did not get so much pay. I used to work in the field and bind grain, keeping up with the cradler; but men doing no more, got twice as much pay...We do as much, we eat as much, we want as much...What we want is a little money...When we get our rights, we shall not have to come to you for money, for then we shall have money enough in our own pockets; and maybe you will ask us for money. But help us now until we get it. It is a good consolation to know that when we have got this battle once fought we shall not be coming to you any more... I am glad to see that men are getting their rights, but I want women to get theirs, and while the water is stirring I will step into the pool. Now that there is a great stir about colored men's getting their rights is the time for women to step in and have theirs...[M]an is so selfish that he has got women's rights and his own too, and yet he won't give women their rights. He keeps them all to himself... |

Not only did women not get their rights, but Black men soon

lost most of

theirs in the rural South.

THE RURAL PERIOD

In the rural period, Black women assumed roles in the system of agricultural production that were similar to those of Black men. They were sharecroppers under the tenant system that emerged to replace slavery. Freed from the restraints of slavery, northern industrial capital rapidly expanded into southern railroads, lumber, and cotton and tobacco manufacturing. Because of racist exclusion, job opportunities outside the tenant system were severely limited for Black men, and only 3.1% of Black women were employed as workers in manufacturing and mechanical trades (and 55% of these women were dressmakers outside the factories). The main jobs of Black women outside of agricultural were in traditional areas of "women's work": 43% of black women were employed in domestic service and 52% - almost all of the remainder - were employed in agriculture.

Angela Davis comments in her work on women:

| During the post-slavery period, most Black women workers who did not toil in the fields were compelled to become domestic servants. Their predicament, no less than that of their sisters who were sharecroppers or convict laborers, bore the familiar stamp of slavery. Indeed, slavery itself had been euphemistically called the "domestic institution" and slaves had been designated as innocuous "domestic servants." In the eyes of the former slaveholders, "domestic service" must have been a courteous term for a contemptible occupation not a half-step away from slavery. |

Domestic

service carried with it the special burden of sexual harassment. Davis

describes what that historically has meant for Black women:

| From Reconstruction to the present, Black women household workers have considered sexual abuse perpetrated by the "man of the house" as one of their major occupational hazards. Time after time they have been victims of extortion on the job, compelled to choose between sexual submission and absolute poverty for themselves and their families. |

The end of slavery caused significant changes in the family. The new economic conditions in the rural South gave the Black family a boost of a strange sort. The survival of the family now depended on its own ability to produce under the brutal tenant system. For Black men, this meant directing the family as an economic unit and exercising more leadership and authority in the family than was possible under slavery. In The Negro Family in America, Frazier described this transformation from the slave system to the tenant system:

| When conditions became settled in the South the landless and illiterate freedman had to secure a living on a modified form of the plantation system. Concessions had to be made to the freedman in view of his new status. One of the concessions affected the family organization. The slave quarters were broken up and the Negroes were no longer forced to work in gangs. Each family group moved off by itself to a place where it could lead a separate existence. In the contracts which the Negroes made with their landlords, the Negro father and husband found a substantial support for his new status in family relations. Sometimes the wife as well as the husband made her cross for her signature to the contract, but more often it was the husband who assumed responsibility for the new economic relation with the white landlord. Masculine authority in the family was even more firmly established when the Negro undertook to buy a farm. Moreover, his new economic relationship to the land created a material interest in his family. As the head of the family he directed the labor of his wife and children and became concerned with the discipline of his children, who were to succeed him as owners of the land. |

The Black family also developed a set of values and ideas to meet their new conditions. Ideas about sexual relations, illegitimacy, and marriage reflected the legacy of an oppressive slavery and the immediate social needs which existed. As Charles S. Johnson reported in his 1934 study, many "marriages" were quite stable as economic and social units, but many Blacks saw no need to seek the legal sanctions which had not been necessary under slavery. Neither was illegitimacy a recognized concept. All children "born out of wedlock" were accepted without stigma and treated on an equal basis by the family and community. Frazier further explicated the Black family that evolved on the heels of slavery:

| Many of the ideas concerning sex relations and mating were carried over from slavery. Consequently, the family lacked an institutional character, since legal marriage and family traditions did not exist among a large section of the population. The family groups originated in the mating of young people who regarded sex relations outside of marriage as normal behavior. When pregnancy resulted, the child was taken into the mother's family group. Generally the family group to which the mother belonged had originated in a similar fashion. During the disorder following slavery a woman after becoming pregnant would assume the responsibility of motherhood. From time to time other children were added to the family group through more or less permanent "marriage" with one or more men. Sometimes the man might bring his child or children to the family group, or some orphaned child or the child of a relative might be included. Thus the family among a large section of the Negro population became a sort of amorphous group held together by the feelings and common interests that might develop in the same household during the struggle for existence. |

Part of the oppression of Black women during this period grew out of the conditions of rural life. Because every available hand was necessary for economic survival, large families were the rule in the rural South. This imposed a tremendous and oppressive burden on Black women. Black women continued as full-time field hands and as full-time housewives and mothers. However, they received no wage payments directly. The resulting economic dependency on men was the concrete basis for the development of ideas about male supremacy (or male chauvinism) that exist even today in this society. Moreover, the male supremacist notion that because women are childbearers they must also single-handedly bear the burdens of childrearing and housework took even firmer hold in this period. Charles S. Johnson, in discussing perceptions of the ideal wife of the rural period, pointed to a man who specified three attributes: "She must be able to work, she must be good looking, and she must be willing to acknowledge him as head of the house." It was a clear articulation of the male supremacist view that the man must be dominant. It is a view that held throughout the rural period and operates to an unfortunate extent even today - in both Black and white families.

Because of the continuing oppression of Black people throughout the rural period, Black women were active in many aspects of the struggle for freedom.

Enfranchisement - Some women (e.g., Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Mary Church Terrell, Ida Wells Barnett, and Mary McLeod Bethune) formed Black suffrage clubs and participated in the women's suffrage campaigns.

Anti-lynching campaigns - Between 1900 and 1914, there were more than 1,079 recorded lynchings of Blacks in the South. Women like Ida Wells Barnett crusaded against lynching. As a newspaper editor in Memphis, she wrote an anti-lynching pamphlet called The Red Record (1895) which resulted in attacks on her newspaper. Her life was threatened and she was eventually forced to leave Memphis, but not before defending herself and going about her work with a six-shooter strapped to her side. As she put it: "I felt that one had better die fighting against injustice than to die like a dog or a rat in a trap. I had already determined to sell my life as dearly as possible if attacked. I felt if I could take one lyncher with me, this would even up the score a little bit." Driven out of the South, she went to Chicago to continue her militant work for Black people's freedom.

The lynchings, as well as the sexual abuse of Black women and attacks on the morality of Black people, motivated women to form the National Association of Colored Women in 1896. The NACW unified Black women and led to the proliferation of women's clubs that addressed not only lynching, but also the social educational, and welfare needs of Black people.

Social uplift programs - Many women dedicated their careers to improving the social conditions of Black people. During the Reconstruction period, hundreds of Black women went South to help establish schools and other institutions designed to aid ex-slaves. Violence was often leveled against Black schools and teachers, especially with the defeat of the Reconstruction governments. But women continued to push for the education of Blacks. Mary McLeod Bethune became one of the most well-known educators, and served as an administrator and advisor in Black youth programs during Roosevelt's "New Deal." Countless women in women's clubs and church organizations also volunteered their time to improve health, child welfare, railroad travel and prison conditions, as well as to build community institutions.

Black

liberation movement - During this period, the struggle for Black

liberation increased its level of organization. The Niagara Movement

(1905) led to the NAACP (1909) and the Urban League was formed in 1911.

Organizations of Black women, like the National

Association of Colored Women, played an important role in founding the

Niagara Movement and were important forerunners of other freedom

organizations.

THE URBAN PERIOD

World War I, which spurred the migration of Black people from the rural South to the city, also pulled Black women off the farms and into the industrial work force. Their experience in the industrial work force during this period was aptly described by Eugene Gordon and Cyril Briggs:

|

In 1917...women were used to replace men, either wholly or partly, in many industries. White women so employed were paid less than the men had been getting, while Negro women received still lower wages. In addition, the Negro women were assigned to the heaviest and most hazardous jobs in the war industries, and to the more menial and grueling work in other lines, such as textiles and clothing factories, food industry, wood-product manufacture, etc... Negro women, tormented by the memory of the drudgery and humiliations of farm and domestic service, happily imagined themselves firmly planted in the industries, with their relatively better conditions. Then came the end of the World War, the collapse of war-time "prosperity" which, because of the correspondingly high cost of living, was confined mainly to the munition barons and other war profiteers and 100 percent "patriots." The crisis of 1921 led to wholesale firing of workers, with the women, and, particularly the Negro women workers, the first to be discharged. Hand in hand with the mass firing went the slashing of wages for those still employed, and the replacement of women workers with the demobilized men at greater speed up and a resultant increase of profits for the employers. Only in the laundry industry, notorious for its high speed-up, low pay and terrible working conditions, and in certain departments of textiles, etc., with similarly bad reputations, were the Negro women able to hold their own. |

By 1930, only 5.6% of all Black women were employed in manufacturing and mechanical industry (as compared to 25% for Black men). But more Black women had moved into the service sector: over 64% in 1930.

World War II drew more Black women into the war-related industries, but once again many were dropped when the war ended. It was clear, however, that service and industrial work had replaced agricultural and domestic work as the main areas of employment for Black women, with service the primary source.

In 1970, of the 2.7 million Black women in the labor force, 25% were service workers (maids, etc.), 21% were clerical workers (like office clerks and secretaries), 16% were operatives (like factory workers), and 18% were private household workers (like maids and cooks). The special oppression of Black women (as compared to white women) is revealed in statistics showing the overrepresentation of Black women in certain occupations (and underrepresentation in certain others). Though they are only 11.4% of the female work force, Black women comprise 65% of all maids, 63% of all household cooks, 41% of all housekeepers, and 34% of all cleaning service workers. Conversely, Black women represent only 4% of all women lawyers and doctors and 5.5% of all women college teachers. Clearly, Black women (along with Black men) have provided U.S. capitalism with essential labor in some of the hardest, lowest-paying, and dirtiest jobs of all the necessary "shit work" of an advanced capitalist society.

We can also use similar statistics to illustrate the triple oppression of Black women in 1980. Class (economic) exploitation, racism, and sexist oppression have combined to put Black women at the bottom rung on most measures of social equality: below white males, Black males, and white females. Table 24 illustrates this.

Table

24

THE TRIPLE OPPRESSION OF BLACK WOMEN, 1980

| White Males | Black Males | White Females | Black Females | |

| Income | ||||

| Mean income for full-time workers | 21,023 | 14,709 | 12,156 | 11,230 |

| Education | ||||

| College (1 or more years) | 37.9 | 22.1 | 28.8 | 20.6 |

| Occupation | ||||

| Professional | 15.8 | 7.8 | 16.9 | 13.2 |

| Clerical and Sales | 12.0 | 10.3 | 42.3 | 33.1 |

| Blue Collar | 45.3 | 56.3 | 13.7 | 15.3 |

| Service | 7.7 | 17.0 | 18.4 | 34.4 |

| Unemployment (1981) | 6.5 | 15.7 | 6.9 | 15.6 |

Source: Based on data in National Urban

League, The State of Black America, 1983, pp. 113, 142, and 152-53.

The integration of

Black women into the urban economy has had a dramatic impact on her role

as a worker and on her role in Black

family life. First, the necessity of working reduces the time that Black

women have to discharge their role as parents. This is even more so with

Black women who are single heads of households. Second, the urban economy

has provided Black women with the economic basis of their independence.

This has freed many Black women from their dependence on Black men that

emerged during the rural period. But this has also increased competition

between Black men and Black women. The historical and continuing

male-supremacy ideology, on the one hand, and the objective economic

independence of Black women, on the other, have in part set the basis for

a struggle.

Black women (and women in general) are punished by existing sexist practices because of their role in the biological division of labor relating to childbirth. For example, an adequate system of sex education, birth control, and family planning is not provided in this society (witness the debate over sex education in the schools and the use of federal funds for abortions). Many young Black women have also been irreversibly sterilized without their knowledge as the price for seeking abortions or family planning assistance! An adequate system of paid maternity leaves is not available. In effect, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1977 that such paid leaves would cost the corporations too much of their profits. The following year, because of the importance of the issue and the pressure of the women's movement, Congress was forced to pass a bill amending Title VII. It mandated that in situations where men were compensated for disabilities, women should receive compensatory pay for pregnancy leaves. However, this applies only to employers who award any disability payments. Low-cost or free daycare facilities still are not available. The point here is that the resources of this society are not allocated to meet the special needs of Black women or women in general - needs which are essential to the very functioning of the society.

Any analysis of Black

women must also take into account the historical imbalance in the ratio of

Black women to Black men, especially in the urban period. Every census

since 1840 has registered more women than men in the Black population.

In

1970, there were 1.1 million more Black women than men. Further, this

varies by locale. The pattern for any particular region, state, or city is

a function of the demand for Black labor in that local

There has been considerable controversy over the concept of the Black matriarchy, or female-dominated family. As we have pointed out, concrete conditions have given rise to the increasing independence of Black women. But the concept of "Black Matriarch" has been overemphasized and often discussed without attention to important facts. Joyce Ladner points to one obvious error in these discussions:

|

The matriarchy has been defined as: "...a society in which some, if not all, of the legal powers relating to the ordering and governing of the family-power over property, over inheritance, over marriage, over the house are lodged in women rather than men." The standards which have been applied to the so-called Black matriarchy depart markedly from this definition. In fact, it has been suggested that no matriarchy (defined as a society ruled by women) is known to exist in any part of the world. |

She also outlines another fallacy in the Black matriarchy thesis:

A popular theme projected by social scientists and in the popular literature is that Black men have been psychologically castrated because of the strong role Black women play in the home and community. Moreover, it is often assumed that the male's inability to function as the larger society expects him to is more a function of his having been emasculated by the woman than the society. Although the scars of emasculation probably penetrated the Black man more deeply than the injustices inflicted upon the woman, there has, however, been an overemphasis upon the degree to which the Black man has been damaged. Some writers on the subject would have us believe that the damage done is irreparable. They also refuse to place the responsibility on the racist society, but rather insist that it is caused by the so-called domineering wife and/or mother. |

For Ladner, the position of the Black man is the fault of the system and not Black women. Lastly, the matriarchal thesis can be faulted because it does not take into account the fact that most Black families consist of both parents, as do most white families. In 1982, 85% of white families and 55% of Black families had two parents. It is among the very poor that the majority are single-parents, for both Blacks and whites, as indicated in Table 25.

The continuing oppression of Black people, and especially Black women, has meant that Black women have continued to be on the front lines of all aspects of the Black liberation struggles throughout the urban period. In the 1930s, Black women were active organizers for CIO unions like the Steelworkers and were active in organizations like the National Negro Congress. Black women led militant protests and demonstrations against unemployment, against discrimination in housing and jobs, and for social welfare legislation. During the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, women like Fannie Lou Hamer of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party inspired oppressed people all over the world by standing up to racist political repression in the South and fighting for her rights. Unheralded, but persistent women like Ella Baker were active in such organizations as the NAACP and SCLC (the Southern Christian Leadership Conference). She was a veteran civil rights worker who guided the spontaneous student sit-in movement toward organizing the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1960.

As the more radical orientation of the Black liberation movement emerged, women were active militants in such organizations as the Black Panther Party, in community struggles, in organizing opposition to war in Vietnam, and in building anti-imperialist support among Black people for the liberation struggles in Africa. Black women have played and are continuing to play leading roles in developing the anti-imperialist and revolutionary orientation of the Black liberation struggle in the United States.

Table

25

PERCENT SINGLE-PARENT FAMILIES AMONG VERY POOR

(UNDER $4,000 PER YEAR) BLACKS AND WHITES, 1960-1975

| Year | Black ( % ) | White ( % ) |

| 1060 | 36 | 23 |

| 1970 | 70 | 47 |

| 1975 | 83 | 63 |

Source.

U.S. Bureau of the Census, The Social and Economic Status of the Black

Population in the United States, p. 108.

Currently, there are significant developments that must be taken into account in discussing Black women and the family. There has been a dramatic increase in the number of families headed by Black women. According to the 1984 Statistical Abstract of the United States, whereas, in 1970 approximately 28% of Black families were headed by women, in 1982 approximately 41% were headed by women. Moreover, in 1982, 47% of all Black children (as compared to 15% of white children) under eighteen were living in female-headed households. Since 1977, over 50% of all newborn Black children were born into families headed by women. Black women and these families suffer a greater share of oppression in terms of income and employment. In 1981, the median income of Black female-headed households was $7,921 as compared to $13,076 for whites.

In addition, the social decay characteristic of advanced capitalism in crisis is increasing the divorce rate among Blacks. All of these forces are beginning to undermine the possibility of strong family relationships. This is especially serious in view of the historical role that the Black family has played in the survival and struggle of Black people for liberation.

The same social crisis, however, also contains its positive seeds. It is creating a greater objective need for and interest in the struggle for Black liberation and social change among Black women who bear a disproportionate burden of the current crisis. The crisis is laying the basis for a collective approach to solving problems that more and more Black women are experiencing along with the entire society.

It is becoming increasingly clear to Black women that their liberation cannot be achieved under capitalism nor in isolation from the masses of working-class Black people. This is a fundamental difference, which distinguishes most Black women from many feminists in the women's liberation movement. Many women (both white and black) in the women's liberation movement in the United States basically accept the capitalist system and simply work toward integrating women into that system on an equal basis. Though they may understand the oppressive nature of patriarchy, many do not see that the capitalist system itself ensures the exploitation of people. This is not how the masses of Black women have analyzed their situation and have plotted the course of their struggle.

in summary, Black women face conditions of oppression and mounting problems that are similar to but also different from Black men. But Black women will continue to go forward to uphold their rich legacy as active fighters for the full freedom of all Black people and an end to their own special "triple oppression". As Frances Beal put it:

The history of our people in this country portrays clearly the prominent role that the Afro-American woman has played in the on-going struggle against racism and exploitation. As mother, wife and worker, she has witnessed the frustration and anguish of the men and women and children in her community and on the job. As revolutionary, she will take an active part in changing this reality. The slave of a slave is a creature of the past. I doubt very seriously, given our history of resistance and struggle. whether working class and poor Afro-American women are going to exchange a white master for a Black one. |

KEY CONCEPTS

| Family | Motherhood | |

| Female-headed household | Population sex ratio | |

| Male supremacy/Sexism | Sterilization/Abortion | |

| Marriage/Divorce | Triple oppression | |

| Matriarchy/Patriarchy | Women's rights movement |

STUDY QUESTIONS

1. What role have Black women played in the economy? Compare the work experience of Black women to white women and Black men in each historical period.

2. What is the "triple oppression" of Black women? Illustrate this concept using historical examples and statistics.

3. What is the current status of "matriarchy" in Black family life? Discuss the historical relevance of this concept.

4. How have Black women contributed to the Black liberation struggle? In what ways have Black women been involved in the struggle against the oppression they face?

SUPPLEMENTARY READINGS

1.

Angela Y. Davis, Women,

Race and Class. New York: Vintage Books, 1983 (first published in

1981).

2. Mari Evans, Black Women Writers (1950-1980): A Critical Evaluation. Garden City: Anchor Books, 1984.

3.

Gloria T. Hull, Patricia Bell Scott, and Barbara Smith, eds., All the

Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of

Us Are Brave: Black Women's Studies. Old

Westbury: The Feminist Press, 1982,.

4.

La Frances Rodgers-Rose, ed., The Black Woman. Beverly Hills: Sage

Publications, 1980.