|

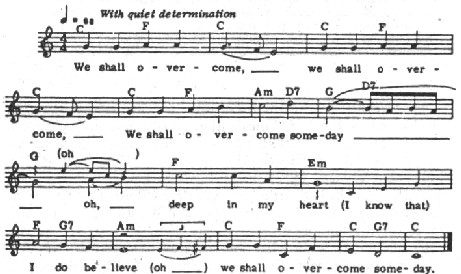

We

Shall Overcome We

shall overcome, we shall overcome, We shall overcome someday Oh, deep

in my heart (I know that), I do believe We shall overcome

someday. This modern adaptation of the old Negro church song I'll Overcome Someday, has become the unofficial theme song for the freedom struggle in the South. The old words were: I'll be all right...I'll be like Him...I'll wear the crown...I will overcome. Negro Textile Union workers adapted the song for their use sometime in the early '40s and brought it to Highlander Folk School. It soon became the school's theme song and associated with Zilphia Horton's singing of it. She introduced it to union gatherings all across the South. On one of her trips to New York, Pete Seeger learned it from her and in the next few years he spread it across the North. Pete, Zilphia and others added verses appropriate to labor, peace and integration sentiments: We will end Jim Crow...We shall live in Peace...We shall organize...The whole wide world around...etc. In 1959, a few years after Zilphia died, I went to live and work at Highlander, hoping to learn something about folk music and life in the South and to help carry on some of Highlander's musical work in Zilphia's spirit. I had no idea at that time that the historic student demonstrations would be starting in the next few years and that I would be in a position to pass on this song and many others to students and adults involved in this new upsurge for freedom. Guy Carawan |

The fight for civil rights is a struggle for the democratic rights guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution. Civil rights are politically defined freedoms, laws that stipulate what groups and individuals can do to fully participate in the society. The Civil Rights Movement is made up of individuals and groups who fight for just laws that in both principal and practice serve to maximize full participation for all people. The Civil Rights Movement thus focuses its attention on the government. It keys in on the contradiction between what the government says in theory (as put forth in documents like the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, etc.) and what the government actually does in practice. The historical basis for the Civil Rights Movement should be understood in the context of the three main historical periods of Afro-American history - slavery, rural, and urban.

Historically, the U.S. government has played an important role in the oppression and exploitation of Afro-American people. For example, the statement, "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal" is found in the Declaration of Independence. But as has been pointed out (see Chapter 13), it was written by slaveowners in the midst of slavery. Furthermore, when the United States successfully fought a revolution to "free itself " from British colonialism, Black people were kept in bondage as slaves. The post-Civil War constitutional amendments (the 13th, 14th, and 15th) established the abstract legal conditions for Black citizens and, along with the Bill of Rights, they provided the legal basis for the Civil Rights Movement. The actual movement, however, did not develop until the 20th century, which saw the rise of monopoly capitalism, the migration of Blacks to the cities, and two world wars in which Blacks fought "to make the world safe for democracy."

During the 20th century, there was a material (economic) contradiction that provided the driving force for the Civil Rights Movement. The masses of Black people were split between two ways of life, between two different conditions of oppression - the rural agricultural experience and the urban industrial experience. In the urban industrial North there was some "civil rights freedom," while in the rural South, particularly in the Black Belt, the white minority used the fascist terror of the lynch mob to force Blacks into submission. The political difference between these two conditions was a matter of the extent to which they were oppressed.

The Civil Rights Movement emerged to confront the contradictions in the U.S. political system. The Civil Rights Movement has been a fight for consistent democracy - a fight against "second class citizenship," against the government's denying Black people the political and civil rights that were guaranteed to white citizens.

In assessing any movement, it is important to sum up the strategy and tactics of that movement. Strategy is the formulation of the main long-range goal that the movement should fight for at a particular stage of development to achieve its main objective. Tactics are the activities which the movement must undertake to respond to the day-to-day ups and downs of the struggle. Thus, for Black people, while the forms or tactics of struggle may change from day to day or year to year (e.g., mass demonstrations vs. petitions), the overall strategy of the movement - how it expects to achieve total Black liberation - will remain unchanged.

The strategy of the Civil Rights Movement in the 20th century is reformist and not revolutionary (though the struggle for civil rights was revolutionary during slavery). It seeks to solve the problems facing Black people under the existing system by using mechanisms which the system has deemed legitimate and acceptable. In essence, the Civil Rights Movement views the U.S. government as positive. "The reason that the government has historically acted against the interests of Black people," the argument goes, "is not because the whole system is rotten and racist, and is manipulated by the dominant economic interests which established it. Rather, racist policies result because good leaders have not been sensitive enough to the moral implications of the system's discrimination against Black people. We need only a few reforms or to elect better individual politicians." Thus, the Civil Rights Movement rules out the need for revolutionary change, a complete and total restructuring of the society which would end the dominant role played by the rich in the economy and government. This revolutionary change is not necessary to solve the problems faced by Black people, they argue.

The tactics of the Civil Rights Movement or any movement must be understood within the context of its strategy. The tactics of the Civil Rights Movement, its day-to-day activity, are reformist as defined by the reformist strategy of the movement. That is, its tactics operate within the confines of accepting the legitimacy of the existing political and economic system and using ways defined by the system in seeking to bring about and protect the civil rights of Black people. Its action has been to work both within the system (e.g., lawyers in courts) and "outside" (protest marches without permits) to mobilize elites (leaders) and the masses of people. It sometimes has engaged in spontaneous short run actions, and other times it has worked through bureaucratic organizations, plodding along in a protracted manner.

The tactics of the Civil Rights Movement have gone through three phases of development. All tactics have been used at all times, but the following order has been the main (chronological) trend: (1) legal action, like court challenges, was the main tactic during the first phase of the modern civil rights struggle, from the emergence of the NAACP through the 1950s; (2) mass action was the main tactic employed during the second phase, which began with the urbanization of Black people during World War II and reached a high point in the 1960s; and (3) electoral politics has been the main tactic which has emerged in the 1970s for the middle-class activists in the Civil Rights Movement.

LEGAL ACTION

The favorite method of struggle for civil rights has revolved around persuading or forcing the legal system (courts, legislature, etc.) to recognize and support the "inalienable rights" of Black people. Two main organizations developed during the almost forty years (1910-1945) when this legal action was the primary tactic of the Civil Rights Movement: the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Urban League.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

The NAACP was formed in 1909 through the merger of two motions: the Niagara Movement and the National Negro Conference. The Niagara Movement was organized in 1905 by W.E.B. DuBois, William Monroe Trotter, Ida Wells Barnett, and other middle-class but militant Black intellectuals. It was a repudiation of the conservative and stifling leadership of Booker T. Washington and the Tuskegee Machine, as can be seen in its founding resolutions:

|

...we believe that

this class of American citizens [Black people] should protest

emphatically and continually against the curtailment of their

political rights... e refuse to allow the impression to remain that the Negro-American assents to inferiority, is submissive under oppression and apologetic before insults... Any discrimination based simply on race or color is barbarous...[D]iscrimination based simply and solely on physical peculiarities, place of birth, color of skin, are relics of that unreasoning human savagery of which the world is and ought to be thoroughly ashamed... Of the above grievances we do not hesitate to complain, and to complain loudly and insistently. To ignore, overlook or apologize for these wrongs is to prove ourselves unworthy of freedom. Persistent manly agitation is the way to liberty, and toward this goal the Niagara Movement has started and asks the cooperation of all men of all races. |

During its four years, the

Niagara Movement carried out a militant program of protest and struggle

against all forms of racist discrimination, especially against lynching.

|

Besides a, day of rejoicing, Lincoln's birthday in 1909 should be one of taking stock of the nation's progress since 1865. How far has it lived up to the obligations imposed upon it by the Emancipation Proclamation? How far has it gone in assuring to each and every citizen, irrespective of color, the equality of opportunity and equality before the law, which underlie our American institutions and are guaranteed by the Constitution? If Mr. Lincoln could revisit this country in the flesh, he would be disheartened and discouraged. He would learn that on January 1, 1909, Georgia had rounded out a new confederacy by disfranchising the negro, after the manner of all the other Southern States. He would learn that the Supreme Court of the United States, supposedly a bulwark of American liberties, had refused every opportunity to pass squarely upon this disfranchisement of millions,...he would discover, therefore, that taxation without representation is the lot of millions of wealth-producing American citizens, in whose hands rests the economic progress and welfare of an entire section of the country. He would learn that the Supreme Court...has laid down the principle that if an individual State chooses, it may "make it a crime for white and colored persons to frequent the same market place at the same time, or appear in an assemblage of citizens convened to consider questions of a public or political nature in which all citizens, without regard to race, are equally interested." In many States Lincoln would find justice enforced, if at all, by judges selected by one element in a community to pass upon the liberties and lives of another. He would see the black men and women...set apart in trains, in which they pay first-class fares for third-class service, and segregated in railway stations and in places of entertainment; he would observe that State after State declines to do its elementary duty in preparing the negro through education for the best exercise of citizenship. Added to this, the spread of lawless attacks upon the negro, could but shock the author of the sentiment that "government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth. Silence under these conditions means tacit approval...Hence we call upon all the believers in democracy to join in a national conference for the discussion of present evils, the voicing of protests, and the renewer of the struggle for civil and political liberty. |

This group was not as militant as the Niagara Movement, but it spoke to liberal concerns and wanted to do something.

That

same year members from the National Negro Conference and the Niagara

Movement joined to formulate the following demands, which laid the basis

for the formation of the NAACP:

|

As first and immediate steps toward remedying these national wrongs, so full of peril for the whites as well as the blacks of all sections, we demand of Congress and the Executive: (1) That the Constitution be strictly enforced and the civil rights guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment be secured impartially to all. (2) That there be equal educational opportunities for all and in all the States, and that public school expenditure be the same for the Negro and white child. (3) That in accordance with the Fifteenth Amendment the right of the Negro to the ballot on the same terms as other citizens be recognized in every part of the country. |

Many Black people, including William Trotter and Ida Wells Barnett, were strongly critical of the dominant role that whites played in the formation of the NAACP.

The NAACP has long been one of the major arms of the Black petty-bourgeois (middle-class) elites - as jobs for lawyers and social welfare professionals, as positions of status for others to speak for the entire Black population, and as a platform for fighting for the kind of "integration" that has expanded opportunities, especially for the middle class. In its early days it led many heroic and courageous struggles against many forms of brutal oppression against Black people. Its legal defense arm has saved many Black people from being legally lynched. The major national accomplishments of the NAACP have been in filing court briefs and lobbying for legislation. During the 1960s, this was the focus of these activities while almost everyone else was out in the streets mobilizing the masses. But in the 1950s the mass movement was just emerging, and the success of the NAACP in the 1954 Supreme Court School Desegregation Decision struck a responsive cord. It stirred the hopes and aspirations of the masses of Black people. By 1962, it had 471,000 members in the 1,500 branches in 48 states. Within the Civil Rights Movement, it is by far the largest organization, with the most resources and the best developed bureaucracy to ensure its ongoing work.

The Urban League The other organization to emerge during this period was the National League of Urban Conditions Among Negroes in 1911, a coordinating council of three organizations: 1) the Committee for Improving the Industrial Conditions of Negroes in New York, formed in 1906 to address the economic handicaps Black workers faced because of both discrimination and the lack of industrial training; 2) the National League for the Protection of Colored Women, organized in 1906 to help Black women migrating from the South to northern cities and facing problems with housing and employment; and 3) the Committee on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, formed in 1910 to study the social and economic conditions of Black people in the cities, to train Black social workers, and to develop agencies to deal with their needs. This umbrella organization later become the National Urban League.

The National Urban League reflected the increased migration of Black people to the cities of the South and North. It also reflected a concern by members of the ruling class that the problems of these new migrants not get out of hand. The Urban League was composed of the same kinds of people as the NAACP - the Black middle class, white liberals, and key representatives of the ruling class. Its first chairperson was Ruth Standish Baldwin, the wife of a leading railroad capitalist who was one of the main financial supporters of Booker T. Washington. In fact, the Urban League was an obvious attempt to counter the militancy of the NAACP with the conservative political line of Booker T. Washington and his ruling-class supporters.

The Urban League carefully avoided the real political issues facing Black people - lynching, the straggle against disfranchisement, etc. Rather, it developed itself as a social service organization - finding jobs, training social workers, and advocating better schools, housing, hospitals, and other facilities for the Black Community. The Urban League did not have a program of struggle, and it failed to have mass appeal and to develop a following among large numbers of Black people. Because of its ruling-class connections, however, it was always one of the civil rights organizations called into consult during "crisis" (e.g., when Kennedy wanted to stop or coopt the 1963 March on Washington).

MASS STRUGGLE

By World War II, Black people were firmly consolidated into the city and into the industrial work force. The mass protests during the Depression, and U.S. preparations to fight another war "to make the world safe for democracy," laid the basis for the second stage of major tactical development in the Civil Rights Movement: mass struggle.

Congress

of Racial Equality (CORE)

The

first new organization to emerge during this stage of mass struggle was

CORE. The early history of CORE is rooted in middle-class idealism, the

reformist approach to "applying Ghandhian techniques of...nonviolent direct action, to the resolution of racial and industrial

conflict in America." The parent group was the Christian pacifist

Fellowship of Reconciliation, and it grew out of student life at the

University of Chicago. After an initial experience with direct action in

1941, a group of fifty people met and formed "a permanent

interracial group committed to the use of nonviolent direct action

opposing discrimination."

CORE has gone through three main stages of development. During its first stage, 1942-1960, CORE was an organization led by an interracial group of integrationists who fought discrimination using nonviolent direct action. Its nonviolent method was based on a certain set of assumptions, as articulated in its statement of purpose:

| First of all, it assumes that social conflicts are not ultimately solved by the use of violence; that violence perpetuates itself, and serves to aggravate rather than resolve conflict. Moreover, it assumes that it is suicidal for a minority group to use violence since to use it would simply result in complete control and subjugation by the majority group. Secondly, the non-violent method assumes the possibility of creating a world in which non-violence will be used to a maximum degree...The type of power which it uses in overcoming injustice is fourfold: (1) the power of active good will; (2) the power of public opinion against a wrong-doer; (3) the power of refusing to cooperate with injustice, such non-cooperation being illustrated by the boycott and the strike; and (4) the power of accepting punishment if necessary without striking back, by placing one's body in the wav of injustice. |

Throughout

this period, it conducted a number of sit-ins, pickets, demonstrations,

and the like in an attempt to achieve its goal of eliminating racial

discrimination.

The early 1960s ushered in a new, stage for CORE, as it led the "Freedom Riders" in a campaign to protest segregated bus depots in the South. In May of 1961, white mobs burned a Freedom Rider bus and Klansmen beat Freedom Riders aboard their buses and in terminals in Alabama. Freedom Riders left Montgomery under the protection of the National Guard, but they were imprisoned immediately upon entering Jackson, Mississippi. These actions for the first time brought national attention to CORE's efforts in the South. After the 1963 March on Washington and the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, CORE shifted from a regional focus on de jure segregation in the South to a national effort confronting de facto segregation in the urban areas. During this period, its membership became predominantly Black and its leadership shifted to Black people who pursued a much more militant version of its previous nonviolent direct action campaigns.

In 1966, CORE entered its third stage. Its leadership remained Black and middle class, but it developed into a Black nationalist organization. Since the late 1960s, it has downplayed mass action and has concentrated on Black capitalism and government-sponsored community development programs. It was very close to and supportive of Richard Nixon. It has even tried to recruit Black mercenaries to fight against revolutionaries in Africa.

Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)

On December 5, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested when she violated the bus segregation ordinance in Montgomery, Alabama. As she explained:

| I had had problems with bus drivers over the years, because I didn't see fit to pay my money into the front and then go around to the back. Sometimes bus drivers wouldn't permit me to get on the bus, and I had been evicted from the bus...One of the things that made this get so much publicity was the fact the police were called in and I was placed under arrest. See, if I had just been evicted from the bus and he hadn't placed me under arrest or had any charges brought against me, it probably could have been just another incident. |

It

was more than just another incident. Four days later, the Montgomery bus

boycott began, and Martin Luther King, Jr. (then only twenty-six) was

elected the president of the Montgomery Improvement Association. Within

slightly more than a year, the buses were integrated.

Following this successful boycott, the SCLC was formed in 1957 to "facilitate coordinated action of local community groups" in the campaigns of struggle that were spreading throughout the South. The SCLC was based in the most powerful social institution in the Black community - the church - and its main source of leadership was the Black preacher in the South. Led by Martin Luther King, SCLC followed the general strategy of all civil rights organizations: "achieving full citizenship rights, equality, and the integration of the Negro in all aspects of American life." To achieve this aim, SCLC adopted some of the tactics used by CORE: voter registration drives, nonviolent direct action, and civil disobedience. SCLC is perhaps best known for several campaigns it waged in cities like Albany, Birmingham, and Selma.

Over 700 people were arrested in a demonstration held in Albany, Georgia in December of l961 to protest the segregation of the city's public facilities. In July of 1962, King and three other Black leaders were convicted of failing to get a permit for that demonstration. Mass protests were held, and throughout that summer more demonstrations and arrests took place.

In

April of 1963, the SCLC launched protests of segregated lunch counters and

restrooms in Birmingham, Alabama. A Birmingham minister, Ed Gardner,

described the campaign:

|

We invited Dr. Martin Luther King and all his staff into Birmingham and we set up workshops and got these people orientated into what we had in mind and into the doctrine of love and nonviolence. These people were to march, go to jail, and whatever the case might occur in our struggle, they were never to fight back, whatever happened. And those who weren't willing to undertake such an undertaking we eliminated, because at that time the segregationists was armed to the teeth. They were prepared for violence and they could handle violence. But we caught 'em off guard with nonviolence. They didn't know what to do with nonviolence, see. We went out to test all the segregation laws, because when we went to court, we had to prove that we were segregated and discriminated against. And the only way we could prove it, we had to try and get put in jail. If we hadn't been willing to go to jail, then the segregation laws would have stood. Because if no one had tried it, then you couldn't prove it in court, even if the judge himself knew it himself, see...The weight of responsibility was on us to prove that we were segregated and discriminated against... When Dr. King came to us, he said, "Now what we're going to have to do, we're going to have to center all our forces here in Birmingham, Alabama, because Birmingham is the testing ground. If we fail here, then we will fail everywhere, because every segregated city and every segregated state is watching which way Birmingham goes. We got to, whatever it takes, break the back of segregation here. We got to do it." He instructed all of us to be ready to pay the price. He said, "Some gon' die, but this is the cost. It'll be another down payment on freedom." So we had these marches. They were tremendous marches. We would have these mass meetings, and then we would leave these mass meetings and march all through the city, one and two o'clock in the morning. Well, the city couldn't rest. |

King was arrested on Good Friday for violating a court injunction against

these protest marches. It was while he was confined over the Easter

weekend that he wrote his now famous "Letter from a Birmingham

Jail" (see Chapter 10).

The following month, the SCLC organized the "children's crusade" in Birmingham, which recruited elementary and high school students into the movement. Police retaliated with police dogs, fire hoses, and mass arrests. One SCLC recruit, Andrew Marrisett, recounted how he became involved in the movement:

|

What really sticks in my mind then and sticks in my mind now is seeing a K-9 dog being sicced on a six-year-old girl. I went and stood in front of the girl and grabbed her, and the dog jumped on me and I was arrested. That really was the spark. I had an interest all along, but that just took the cake - a big, burly two-hundred-and-eighty-five-pound cop siccing a trained police dog on that little girl, little black girl. And then I got really involved in the Movement. That changed my whole way of thinking. I was born a great Baptist. All my life I'd been through the Sunday School thing and the Bible School and church on Sunday morning and in the afternoon and at night and prayer meetings and choir rehearsals and traveling around. I was into that Christian thing, like most of my people are now, where they're so blindly engrossed,...not really looking at what was going on around them... I knew something was wrong, but...I didn't have any idea of the value of being able to go to every counter in the store, including the lunch counter. I had read about Greensboro. I knew about the sit-ins when they started here, but it just didn't ring no bell. So I always tell people that dog incident really rung my bell. |

The Birmingham demonstrations signaled a profound change in the direct-action campaigns in the South. As Bayard Rustin put it in 1963:

|

For the black people of this nation; Birmingham became the moment of truth. The struggle from now on will be fought in a different context... For the first time, every black man, woman and child, regardless of station, has been brought into the struggle. Unlike the period of the Montgomery boycott... the response to Birmingham has been immediate and spontaneous. Before Birmingham, the great struggles had been waged for specific, limited goals. The Freedom Rides sought to establish the right to eat while traveling; the sit-ins sought to win the right to eat in local restaurants; the Meredith case centered on a single Negro's right to enter a state university. The Montgomery boycott, although it involved fifty thousand people in a year-long sacrificial struggle, was limited to attaining the right to ride the city buses with dignity and respect. The black people now reject token, limited or gradual approaches. The package deal is the new demand. |

On the heels of Birmingham came the March on Washington in August of 1963, and it was there that Martin Luther King delivered his now famous "I Have a Dream" speech, a part of which is excerpted:

|

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the, long night of captivity. But one hundred years later, we must face the tragic fact that the Negro is still not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. So we have come here today to dramatize an appalling condition... It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment and to underestimate the determination of the Negro. This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. 1963 is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the Nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our Nation until the bright day of justice emerges. But there is something that I must say to my people...Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny and their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone... I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive... I say to you today, my friends that in spite of the difficulties and frustrations of the moment I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: "We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal."... With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day... When we let freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God''s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, "Free at last! Free at Last! thank God almighty, we are free at last!" |

For Martin Luther King and many others (both Black and white) the March on Washington was a symbol of hope - that Blacks and whites could work together, using a nonviolent approach, to bring about change for Black people. The march had been designed to broaden the base of support, to bring in white moderates and white labor to address not only civil rights but also the problems of the working class - unemployment and poverty. King became the embodiment of that hope.

In

contrast to Martin Luther King and reformism was Malcolm X, who held the

revolutionary notions that the society needed to be

restructured and that the necessity of violence to transform it ought not

be ruled out. Not surprisingly, he had a different view of the March on

Washington, which he described in his auto-biography:

|

Not

long ago, the black man in America was fed a dose of another form of

the weakening, lulling and deluding effect, of so-called

"integration." It as that "Farce on Washington,"

I call it... Overalled rural Southern Negroes, small town Negroes, Northern ghetto Negroes, even thousands of previously Uncle Tom Negroes began talking "March!"... Groups of Negroes were talking of getting to Washington any way they could - in rickety old cars, on buses, hitch-hiking, walking even if they had to. They envisioned thousands of black brothers converging together upon Washington - to lie down in the streets, on airport runways, on government lawns - demanding of the Congress and the White House some concrete civil rights action. This was a national bitterness; militant, unorganized, and leaderless. Predominantly, it was young Negroes, defiant of whatever might be the consequences, sick and tired of the black man's neck under the white man's heel... The government knew that thousands of milling, angry blacks not only could completely disrupt Washington - but they could erupt in Washington... Any student of how "integration" can weaken the black man's movement was about to observe a master lesson. The

White House, with a fanfare of international publicity,

"approved," "endorsed," and "welcomed" a March

on Washington The next scene was the "big six" civil rights Negro "leaders" meeting in New York City with the white head of a big philanthropic agency... Now, what had instantly achieved black unity? The white man's money. What string was attached to the money? Advice. Not only was there this donation, but another comparable sum was promised, for sometime later on, after the March...obviously if all went well. The original "angry" March on Washington was now about to be entirely changed... Invited next to join the March were four famous white public figures: one Catholic, one Jew, one Protestant and one labor boss. The massive publicity now gently hinted that the "big ten" would "supervise" the March on Washington's "mood," and its "direction." The four white figures began nodding. The word spread fast among so-called "liberal" Catholics, Jews, Protestants and laborites: it was "democratic" to join this black March. And suddenly, the previously March-nervous whites began announcing they were going. It

was as if electrical current shot through the ranks of bourgeois

Negroes - Those "integration"-mad Negroes practically ran over each other trying to find out where to sign up. The "angry blacks" March suddenly had been made chic... Who ever heard of angry revolutionists all harmonizing "We Shall Overcome...Suum Day..." while tripping and swaying along arm-in-arm with the very people they were supposed to be angrily revolting against? Who ever heard of angry revolutionists swinging their bare feet together with their oppressor in lily-pad park pools, with gospels and guitars and "I Have A Dream" speeches?The very fact that millions, black and white, believed in this monumental farce is another example of how much this country goes in for the surface glossing over, the escape ruse, surfaces, instead of truly dealing with its deep-rooted problems. What that March on Washington did do was lull Negroes for a while. |

The

masses were not lulled for long. less than a month after the March on

Washington, four Black children died in the bombing of a Birmingham

church. During the "long hot summer" of 1964, there was

unprecedented racial violence in the cities and against hundreds of

volunteers who had gone to Mississippi to work on voter registration

drives and other projects. On March 7, 1965 (what was to became known as

"Bloody Sunday") state troopers and Dallas county deputies beat

and gassed demonstrators marching for voting rights in Selma, Alabama.

The following week, President Johnson announced that he was sending a

voting rights bill to Congress, but the marches continued. So did the

violence against civil rights marchers. More and more people in the Civil Rights Movement

were questioning the nonviolent approach advocated by the SCLC.

During the early 1960s, most of the SCLC campaigns focused on local governments that denied Black people access to public facilities, though some dealt with voting rights and voter registration in the South. In the late 1960s, the SCLC organized a massive march to Washington called the Poor People's Campaign, and later took up the fight against racism in northern cities like Chicago.

While SCLC was anchored in the church, it revolved around the charisma of Martin Luther King. Thus, rather than surviving as a major force after King's death in 1968, SCLC became split as King's lieutenants moved on down separate paths, competing with each other for the authority of King's leadership and legacy.

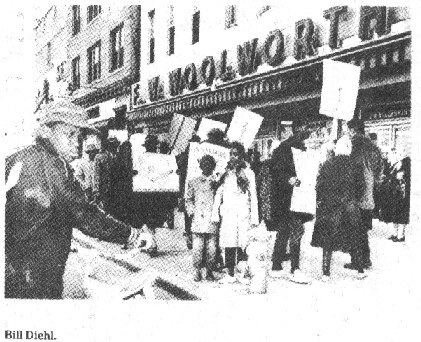

Student

Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

SNCC emerged in 1960 as the organizational consolidation of the

spontaneous student sit-in movement that had begun in Greensboro, North

Carolina when four Black students sat in at a Woolworth's lunch counter

which refused to serve Black people.

SNCC was initially under the ideological and political leadership of King and SCLC. It advocated "the philosophical or religious ideal of non-violence" as the basis of its orientation and action and its goal was integration. The students were initially based on the campuses in the South. However, SNCC activists soon left college campuses and went into the Black Belt rural South. They directly confronted what remained of the lynching-mob terror by forming solid links with the rural masses and engaging in direct action.

SNCC went through three stages. From 1960 to 1963, SNCC was based in the South and developed militant campaigns to focus attention on the denial of democratic rights to Black people, especially in the rural areas. This was a period of petty-bourgeois, religiously inspired idealism. It was not the U.S. system but the rejection of Blacks by that system that SNCC fought against. SNCC activists believed in the American Dream.

The sit-ins they conducted hit the country like a bombshell and spread like a prairie fire. In a year's time, more than 50,000 students were involved in over 140 places. SNCC's sit-in tactics set the tone for all civil rights activity during this period. The sit-ins led to the freedom rides initiated by CORE, with SNCC joining in when they were confronted with mob violence.

After the sit-ins and freedom rides, students began to voluntarily leave school to work full-time for SNCC. They plunged deep into the South. One group focused on the struggle to desegregate public accommodations. The other stressed the need to register voters and to struggle for change through the ballot.

The second period of SNCC's development (1963 to 1964) was a time of transition. In these years, SNCC used the momentum of its successful sit-ins to seize a national platform and to pull the nation's attention to the deep South. A key participant in the 1963 March on Washington, SNCC was regarded as a brash, young militant organization (in fact, SNCC speaker John Lewis was forced to delete the most militant portions of his speech). SNCC had long since dropped its college appearance and had adopted the denim overalls of the Mississippi sharecropper as its uniform for struggle.

In February of 1964, SNCC sent out a call for Black and white students throughout the nation to come to work in Mississippi for the summer. Nearly 1,000 volunteers worked in Mississippi that summer. During those months, 6 people, were killed, 80 beaten, 35 churches burned, and 30 other buildings bombed. But the nation was forced to look at Mississippi, a state dripping with the venom of racism.

This period sparked a reconsideration of nonviolence. Bob Moses, a leading SNCC militant in Mississippi, captured the essence of the struggle within the organization when he said of Martin Luther King's philosophy:

| We don't agree with it, in a sense. The majority of the students are not sympathetic to the idea that they have to love the white people that they are struggling against. But there are a few who have a very religious orientation. And there's a constant dialogue at meetings about non-violence and the meaning of non-violence...For most of the members it is a question of being able to have a method of attack rather than to be always on the defensive. |

The

great political lesson of this period was learned when SNCC tried to break

the domination of the regular Democratic Party in Mississippi by

organizing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). After holding

legal precinct, district, and state elections, the MFDP went to the

Democratic convention in Atlantic City. The MFDP delegates had a sound

case, but vice-presidential hopeful Hubert Humphrey, acting on President

Johnson's instructions, set up a compromise. The MFDP delegates would

have representative seating, but they would have no voice and no vote. All

established civil rights leaders (King from SCLC, Wilkins from the NAACP,

Rustin from the A. Philip Randolph Institute, etc.) urged acceptance of

this compromise. But SNCC, insisting that they had made too many

sacrifices to compromise their principles, rejected the plan.

The grass-roots MFDP delegates stood by SNCC, the youthful militants who had walked with them down the dusty roads to register to vote. The lesson they all learned was that the Democratic Party could not be relied upon to contribute to the liberation of Black people. As one militant put it: "The next logical stop is the call for Black power." It was a step that was facilitated by SNCC groups that had been emerging in northern cities. There they already had moved beyond simple support work for the southern struggle and had begun to fight against racism and oppression in the urban areas of the North.

The third period lasted from 1965 to 1967. A trip to Africa by several SNCC leaders, discussions with and about Malcolm X, and growing alienation between Blacks and whites inside SNCC was capped by the Watts riot in August, 1965. The following June, "Black Power" became SNCC's battle cry in a march led by James Meredith in Mississippi. The latent nationalism of Black people - who had childhood roots in the rural South, had relatives still living there, and had continued to experience national oppression in the North - surged forward.

By 1967, the Black liberation movement was at an all-time high. SNCC, however, still had not developed a scientific analysis of this society and did not have a systematic program. Consequently, it began to rely more on its leading personalities, the media, and its influence on other organizational forms. Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown (as, heads of SNCC) became household names in the United States, but there was no coherent political plan to carry the movement forward.

During 1967, SNCC developed an anti-imperialist stand on many international issues. It also sent delegations to Europe, Japan, and the Third World to support "liberation groups struggling to free people from racism and exploitation." In condemning "expansionist Zionism backed by U.S. imperialism" after the June War in the Middle East, SNCC alienated itself once and for all from the liberal philanthropists who had financed the Civil Rights Movement. The leadership then turned to the Black Panther Party as a new organizational form, but their relationship was short-lived. SNCC continued, but the staff was tired, disillusioned, and demoralized by the lack of organization, strategy, and (most of all) a systematic, coherent political line.

SNCC's major weakness was its consistent lack of a unified line and political education, which made it more difficult to move forward. This resulted in great gaps developing between the rank-and-file militants in local projects and its central leadership. Moreover, it made it difficult for SNCC to consolidate and make shifts of position when necessary. This was the basis for the other problems. First, because SNCC lacked a revolutionary strategy, each campaign raised ultimate hopes only to lead to great disappointments, disillusion, and anger. Second, SNCC depended more on key personalities rather than on organizational structure and process. Many SNCC leaders thus appeared larger than life, and their weaknesses became magnified liabilities for the entire organization. Third, SNCC's program was characterized by bowing to spontaneity, a process of seizing on the objective motion of people and calling that revolutionary. Moreover, sometimes a major campaign would start accidentally and be allowed to disrupt ongoing work. Finally, all of these problems were complicated by SNCC militants' not having the discipline of relating to each other in the most principled way, particularly in interpersonal relations.

These shortcomings were glaring not because SNCC was a total failure, for it had some measure of success. SNCC was committed to the masses of Black people, and had no hesitancy in sinking deep roots among them. It was a bold, fearless army of militant Black youth, who sought out the most dangerous area to show Black people that it was possible to fight oppression and win. It had an ability to develop slogans that were adopted by the masses, to use songs to mobilize and raise the spirit of the masses, to project symbols that fired the imagination of the Black masses, and generally to use records, still photography, films, and newspapers in carrying propaganda work deep among the masses. But SNCC did not survive. Its reliance upon personalities and its failure to develop correct strategy and tactics lead SNCC away from deepening its ties with the masses of Black people and building a mass base as the key to the Black liberation struggle.

ELECTORAL POLITICS

Electoral politics as a tactical development of the Civil Rights Movement is a logical and expected outcome of the previous stages . Two factors laid the basis for this stage. First because of the reformist nature of the Civil Rights Movement - that is, operating within the existing political system - voting and voter registration were key tactics. The ruling class, through various foundations and private and public agencies, pumped millions of dollars into the voter-registration projects. Black registration in the South almost doubled to a total of about 2 million between 1962 and 1964. Second, the power of the Black vote was established. In 1960, for example, the election of Kennedy was determined by Black voters. Increasingly, Black people sought political office, especially in urban areas where the Black vote was concentrated. The result has been a significant increase in both Black elected politicians and appointed officials. White politicians of both parties now seek to influence and win over Black voters.

Thus, the leadership of the struggle for civil rights has increasingly shifted away from those advocating mass action and to those who have faith in electoral politics. Such organizations as the Congressional Black Caucus, the National Black Political Assembly, and the National Association of Black Local Elected Officials are manifestations of the new electoral tactic (see Chapter 13).

There is another aspect of the ruling-class strategy to diffuse the militancy of mass struggle among Black people. Many of those who were leaders in the Mass campaigns of the 1960s have been coopted into the system as legislators (Julian Bond of Georgia), mayors (Marion Barry of Washington, D.C.), and even ambassadors (Andy Young, United Nations). These leaders have adopted the view that Black people have passed the stage of mass protests and "being in the streets" is no longer the main tactic in the Black liberation movement.

The high points of this phase of the movement are the recent successful electoral campaigns of Harold Washington (first Black mayor of Chicago) and of Rev. Jesse Jackson (for president of the United States, placed third in the Democratic National Convention). These two elections sparked unprecedented mass involvement by Blacks in voter registration and turnout. Many political analysts believe that Blacks have become a permanent part of big city and national politics.

In summation, the main strength of the Civil Rights Movement during its phase of mass action in the 1950s and 1960s was its orientation toward struggle. Because the masses of Black people took their demands to the streets, they achieved many concrete gains. On the federal, state, and local level in all branches of government - executive, legislative, and judicial - laws and policies were adopted which brought the government's practice more in line with its promises regarding equality of treatment regardless of race.

This turn away from struggle is the real weakness of the current electoral politics phase of the Civil Rights Movement. The masses of Black people are now being told that "Blacks have outgrown the need for street demonstrations; we have become more sophisticated. Electing Black politicians and relying on them is the most effective path to achieving Civil Rights." This is not the first time that such a course of action has been advocated. In fact, it is this question of strategy - accepting a reformist approach to the struggle for the democratic rights of Black people - that has been the historical weakness of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.

The futility of a reformist approach to the solution to Black people's problems can be seen in the 1980s struggle concerning the Civil Rights Commission. The Civil Rights Commission was a federal body consisting of commissioners who were appointed by the President and usually served until they voluntarily resigned or died. The Commission had no powers other than to inform the public about civil rights and recommend policy to Congress and the President. Since it was set up in 1957, the Commission had maintained an appearance of being bipartisan and independent.

President Reagan proved himself an opponent of this tradition when he began to dismiss commissioners and to appoint others who shared his ideological beliefs. Further, he made a move to dominate the Commission, first by appointing a new chairperson, and then by attempting to appoint a majority of the members. The major civil rights organizations made vigorous protests and convinced Congress to withhold support from the President. A compromise was worked but so that now the President gets to appoint half of the commissioners and Congress the other half. This is a dramatic story of how the President challenged the major agency in the federal government focusing on civil rights. Though the Civil Rights Movement influenced Congress to negotiate a compromise, it did not provide full and adequate defense since the Commission is now highly politicized and is likely to be challenged again in the future.

This

discussion of the fight for civil rights might well end here because it is

ending on the ambiguity of compromise. In this case, it is the compromise

of the civil rights forces with a conservative executive of the federal

government. It produced the net effect of moving to the right. In the

1980s, the fight for civil rights is no longer merely holding onto the

things that were won in the 1960s. We have entered the period of trying to regain the things that were

won in the 1930s. Further, it is this fight for democratic rights that

puts Black people at the heart of people's movements in the United States

because all types of interests get served by making socio-political life

more democratic.

KEY CONCEPTS

| Civil disobedience | Mississippi Freedom | |

| Civil rights/Democratic rights | Democratic Party | |

| Electoral Politics | Nonviolence | |

| Legal action | Reform/Revolution | |

| Mass action | Second-class citizenship | |

| Strategy/Tactics |

STUDY QUESTIONS

1. Discuss the three phases in the historical development of the Civil Rights Movement. Identify and compare the strategy and main tactics used during each phase.

2. Discuss the origins and initial programs of the five major organizations to emerge during the modern Civil Rights Movement. What are their main similarities and differences relative to the strategy and tactics of the overall movement?

3. Compare and contrast the social composition, organizational development, political orientation, and program of action of the NAACP and SNCC.

4. Does the Civil Rights Movement lead to reform or revolution? Explain.

SUPPLEMENTARY READINGS

1.

Clay Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Cambridge:

Harvard University Press, 1981.

2. Langston Hughes, Fight for Freedom, the Story of the NAACP. New York: W. W. Norton, 1962.

3.

David levering Lewis, King: A Biography. 2d ed. Urbana: University

of Illinois Press, 1978.

4.

Doug McAdam, Political Process and the

Development of Black

Insurgency, 1930 - 1970. Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 1982.