|

Yet

do I marvel at this curious thing: Countee

Cullen, "Yet Do I Marvel," 1925. All

I can say is that when I was a boy we always was singin', you know,

just hollerin'. But we made up our songs about things that was happenin'

to us at the time, and I think that's where the blues started. Son

House of Mississippi, 1971 I

don't think I'm singing. I feel like I am playing a horn. I try to

improvise like Les Young, like Louis Armstrong, or someone else I

admire. What comes out is what I feel. I hate straight singing. I have

to change a tune to my way of doing it. That's all I know. Billy Holiday, Hear Me Talkin' to Ya, 1955. |

Black

culture is of major significance in the study of the Afro-American

experience. Historically, considerable controversy has existed around the

question of the origins and content of Black culture. Even in this period of

the deepening social, political, and economic crisis of monopoly capitalism,

Black culture continues to be a significant source of cohesion among Black

people.

Culture

is a key aspect of the development of a nation. This is also true of

Afro-Americans as a distinct nationality. Its development reflects the

similarities and differences between Black people and the entire society.

It also reflects the similarities and differences - especially differences

based on class - that exist among different groups of Black people.

Culture (in form and content) is historical and Black culture is no exception. Just as the historical stages of the Black experience reflect changes in the mode of material (economic) production, so cultural change reflects changes in the mode of cultural production. In other words, similar factors are involved in how Black culture is produced: What technology is used? What numbers of people with what kinds of skills are involved? Who owns what? And who works for or with whom? The mode of cultural production is thus dependent on the mode of material production. Furthermore, the historical development of Black culture reflects the same historical periods as all other aspects of the Black experience. It is especially important to begin with Africa.

TRADITIONAL

AFRICAN CULTURE

The

development of Afro-American culture has its roots in sub-Saharan Africa

before the slave period. The pattern of cultural development in Africa

reflects both similarity and diversity. African societies were similar in

that most were pre-literate (had no formal written language) and therefore

relied heavily on the oral tradition. Moreover, many African societies

were relatively small and, therefore, generally developed strong social

controls (as opposed to legal codes) to regulate behavior in such areas as

property rights and sexual relations.

The level of cultural development among groups in Africa varied according to the level of technological development, which reflected different concrete conditions and stages of development. Some societies in Africa had some of the highest levels of technology in the world. For example, a society in East Africa had a method of forging iron a thousand years before the process was discovered in Europe in the 19th century. Most societies, however, were less technologically developed than Europe, particularly in the crucial area of weaponry. Europeans thus came to dominate Africa and to retard its technological development further. Similarly, African cultural development was fundamentally altered by European imperialism and colonialism.

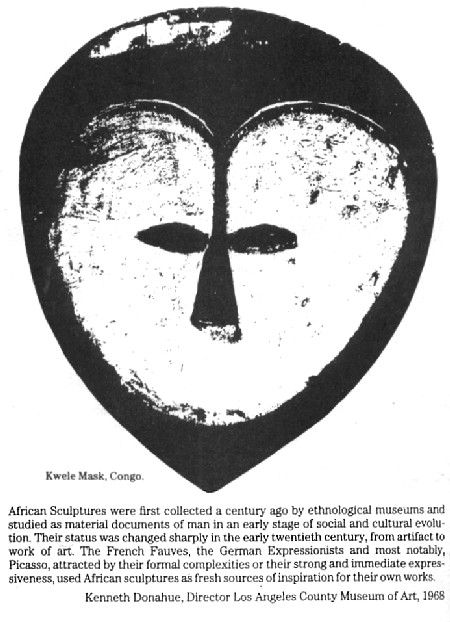

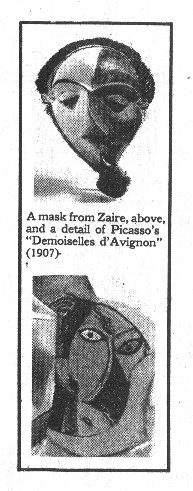

The

African arts were more advanced and more developed before European

colonialism than after. The pattern of "cultural borrowing" that

took place between Europe and Africa underscores this. The impact of

African art can be seen, for example, in 20th century modern Europe art,

which reflects West African sculpture done before colonialization. The art

of the Dan, Bakota, and Baule (among others) was discovered by the modern

artists in the first showing of "primitive" art in Paris. This

exposure had a major impact on the development of the cubist school of art

(led by Picasso and others). The colonial domination of African societies,

however, stifled African cultural development. It was only with the demise

of European colonialism that African culture began to flower once again.

A

new African culture has emerged, especially in African countries that have

fought wars of national liberation. African culture is not now limited to

the pre-colonial "tribe" but reflects the emergence of new

national culture. For example, instead of separate "tribal" or

ethnic cultures, we now have the emergence of new Mozambican culture.

There

has been considerable discussion about the necessity of reconstructing

"traditional" African culture. A study of the current

developments in Africa, however, will reveal two important considerations

regarding culture: (1) the continuing role of cultural aggression and

cultural genocide as part of imperialist domination in Africa; and (2) the

role of cultural resistance as a weapon in the fight to end imperialism

and the use of culture in consolidating new post-colonial African nations.

The latter involves creating a genuine national culture, a new national

unity that transcends the many religious, ethnic, geographical, and other

differences that imperialism has been able to use to further divide and

weaken African peoples.

The important point to remember with respect to Afro-American culture is

that Africa had a rich cultural heritage, which African people brought

with them to the Americas during the slave trade. Africa thus provided the

basis for what was to develop as Afro-American cultures.

THE

SLAVE PERIOD

Afro-American culture which emerged under slavery, however, was not based solely on African cultural tradition. Those who hold such a position today fail to reflect on the fundamental transformation of Africans becoming Afro-Americans - a new people with profound historical and symbolic links to Africa, but with a new material reality and a new cultural reality.

Cultural

"creolization" best describes this process of transformation.

Creolization is a process in which two people and two cultures interact,

with one people taking on the characteristics of the resulting (cultural)

synthesis. For Black people in the United States, this cultural

creolization has involved two complex and dynamic aspects:

1. Among Africans themselves, a creolization process developed as Africans captured from different places and from different cultural backgrounds were forced to live together under the conditions of the slave trade and slavery. A process of mutual cultural exchange and synthesis took place.

2. Almost simultaneously, this dynamic mixture of African cultures was interacting and exchanging with European cultures, which were themselves varied because of the different national identities and cultural patterns of the oppressive slave traders and plantation owners, (British, French, etc.).

Thus, this process of creolization or cultural transformation (which Africans were going through within the institution of slavery in the Americas) has two distinct yet inter-related dimensions, two ways in which Africans were being transformed into Afro-Americans. One was the loss or continued survival of African cultural traits. The other was the adoption and internalization of the new cultural expression in the Americas. Both led to the development of Afro-American culture.

This process of creolization was determined by the conditions of forced labor and total social control under slavery. Thus, we can identify a continuum, based on structural features of the slave system, that reflects degrees of creolization or cultural transformation among Black people during slavery.

Runaway

slave communities - The maroons of Jamaica and the "geeche"

or "gullah" people of the Sea Islands off the Georgia and South

Carolina coast preserved African cultural traits to the most significant

degree.

Creolization still characterized these areas, but because of historical

isolation, these areas have appeared to be "most African" over

the years. This was the main point proved ,by the work of linguist Lorenzo

Turner and anthropologist Melville Herskovitz.

Field Slaves - The conditions of working from "can't see in the morning to can't see at night," the terror of the overseer's whip, and segregated social life on the plantation nurtured key cultural developments The social organization of slaves lent itself to the development of distinct culture, which John Blassingame describes:

| The social organization of the quarters was the slave's primary environment which gave him his ethical rules and fostered cooperation, mutual assistance, and black solidarity... The slave's culture or social heritage and way of life determined the norms of conduct, defined roles and behavioral patterns, and provided a network of individual and group relationships and values which molded personality in the quarters. The socialization process, shared expectations, ideals and enclosed status system of the slave's culture promoted group identification and a positive self-concept. His culture was reflected in socialization, family patterns, religion, and recreation. Recreational activities led to cooperation, social cohesion, tighter communal bonds, and brought all classes of slaves together in common pursuits. |

House slaves - These conditions were conducive to the greatest degree of cultural assimilation, meaning that so much of the slaveowner's culture was borrowed by the house slaves that they became the most "Euro-Americanized" of all Afro-Americans.

Urban

slaves - The city was the center of cosmopolitan and dynamic cultural

interaction, and the lives of slaves reflected this. There was a great

deal more freedom of movement for the slaves in the city, and two lines of

cultural development resulted: the sacred and the profane, or the culture

rooted in the church and that rooted in the barroom.

Music

is the best example of the cultural diversity that emerged during the

slave period. Many other aspects of cultural life (sculpture, African

languages, traditional African religious rituals, and so forth) were

prohibited and were penalized. Music, however, flourished.

Many communities of runaway slaves maintained the drum and the basic features of traditional African music. Even when they had no drums, they would practice "patting juba." Patting juba involved, as Solomon Northup described it, "striking the hands on the knees, then striking the hands together, then striking the right shoulder with one hand, the left with the other - all the while keeping time with the feet, and singing... " The field slave was the collective author of many spirituals. Spirituals might be thought of as the Africanization of Christian cultural expression based on the painful experience of being a slave. Field slaves also sang folk songs reflecting their secular life, as Blaissingame points out:

| The secular songs told of the slave's loves, work, floggings, and expressed his moods and the reality of his oppression. On a number of occasions he sang of the proud defiance of the runaway, the courage of the black rebels, the stupidity of the patrollers, the heartlessness of the slave traders and the kindness and cruelty of masters. |

House

slaves were frequently used to entertain the slave master, and for this

reason they were taught to perform European music as white people did it.

Urban slaves were caught in the dynamic cultural explosion of the city,

and they began to develop the rudiments of jazz.

In

addition to music, slaves relied on the oral tradition, much as their

African ancestors did. Blassingame outlines the use to which folk tales

were put in the slave environment:

| Primarily a means of entertainment, the [folk] tales also represented the distillation of folk wisdom and were used as an instructional device to teach young slaves to survive. A projection of the slave's personal experience, dreams, and hopes, the folk tales allowed him to express hostility to his master, to poke fun at himself, and to delineate the workings of the...system. At the same time, by viewing himself as an object, verbalizing his dreams and hostilities, the slave was able to preserve one more area which whites could not control. While holding on to the reality of his existence, the slave gave full play to his wish fulfillment in the tales... |

This slave culture, synthesizing elements of African cultures, Euro-American cultures, and the slave experience, was the foundation for the Afro-American national culture that emerged during the rural period.

THE

RURAL PERIOD

After the Civil War and Reconstruction, a distinct national culture emerged that unified the Afro-American people, especially in the Black Belt South. This new national culture of the Afro-American people was conditioned by the structural constraints of the new historical period. The economic and political repression of the rural tenancy period kept Black people poor, uneducated, and relatively stationary on the land. In this sense, it was a restrictive and limited social world. On the other hand, it was not slavery, and the intimate control of plantation life by slaveowners and overseers did not exist. There was some degree of freedom.

The

oppressive character of the economic and political structures of Black

rural life and the little freedom that did exist provided the context in

which Black culture developed in the rural period. A two-sided,

dialectical character to the Black experience developed: (1) the

individual tenant farmer's family life that revolved around the yearly

cycle of farming, and (2) the collective life of the community on Saturday (market day) and Sunday (church). A contradiction existed

between the isolated individual life on the farm and the collective

cultural experience for the entire community on Sunday at church.

Everyday, cultural life was molded by the poverty of subsistence farming,

while collective cultural development took place around the church and

included food preparation, music, recreation, moral training, ritual

observance of life stages (christening, baptism, marriage, and funerals),

etc. In general, then, the family was associated with both aspects of this

dialectical cultural existence. It reflected both the necessities and the

freedom of tenant farming and rural life.

The development of a nation has generally reflected the drive of an emerging bourgeois class to control its own market, to run its own turf (so to speak), and to facilitate its own development. Correspondingly, national culture is dominated by this class as well. Imperialism and racism stunted the development of the Afro-American nation, especially in blocking the development of a Black bourgeoisie. Because of this, the Black church, as a social institution that did develop, has played a very important role in the Afro-American nation. The Black preacher emerged as a personification of the cohesiveness and national unity of Black people. The preacher was one of the main vehicles for the spread of Afro-American culture and Afro-American national conscious ness, especially among the Black middle class or petty bourgeoisie. In addition, the church was the basis for the collective expression of Afro-American national development in the area of economic life, because it was through the church that mutual aid societies and the like developed. This role of the church in Afro-American national development is the basis for the continued pivotal role of the church among Black people.

While the Black church was the main expression of the rising bourgeois cultural domination over the Black community during this period, it was not the only cultural dimension. The masses of people were not all socially organized into families that participated in the "morally righteous" context of the church. There were the unattached individuals whose cultural lives revolved around the more immediate pleasures and emotions of the beer hall, cafe, and brothel. This might be summed up as the contra- diction between Saturday night and Sunday morning, with a significant number of people (especially males and especially before marriage) participating in both. This cultural contradiction is manifested musically in blues and gospel music, both of which fully emerged during this period.

THE URBAN PERIOD

The

urban period brought decisive, qualitative changes in the economic and

political conditions of Black people. It also introduced new developments

in Afro-American culture. Not only did the general cultural life of Black

people change, but for the first time full-blown, self-conscious arts

movements developed among Black people. How was the urban experience

different from the rural period such that new cultural forms could emerge?

First, the seeds of Black urban culture did exist during slavery and the

rural period. However, the mode of cultural production was limited by the

overall class relations, social context, and technological possibilities.

The urban period, beginning around World War I, gave Black culture greater

access to the American mainstream and the mainstream greater access to it.

Second, when Blacks moved en masse to the city there was no immediate

transition, but rather one that took several generations to develop. There

were three major forces which operated to transform Black culture during

this period.

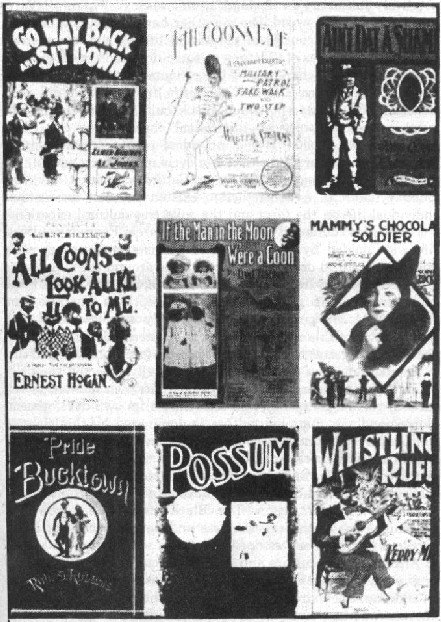

Migration and urbanization - World War I caused mass migrations of Blacks out of the South, which led to the concentration of Blacks into ghettos of northern urban centers. City life was less centralized and less intimate than rural life had been, and Black culture reflected this greater variety. Through the radio, movies, night clubs, and just being in the city, Black people had more access to and were more influenced by the cultural patterns of other nationalities (and in turn exercised considerable influence on other cultures).

Proletarianization - The daily work experience of Black people was transformed from mainly agricultural work on the farm to factory work in large industries alongside white workers and to the urban service sector (as maids, pullman porters, etc.). The new conditions, and the newer forms of struggle which emerged, provided new experiences on which the cultural and artistic creativity could draw. In addition, industry's need for a better trained labor force meant that Black people had greater access to education. A more literate population and cultural artists who were skilled in various crafts resulted.

Commercialization

- Black culture and the arts ceased to be something developed by

Blacks for their own personal consumption and enjoyment. Its products

became commodities, products of the capitalist system available to anybody

who had money enough to pay. With soul food, the commercialized form was

the restaurant. With dance, it was night clubs. With music, there were

the big bands, night clubs, and the recording industry. And with writing,

an outpouring of poems, novels, short stories, books, and magazines. In

the slave period, Black culture was essentially underground. During the

rural period, it was isolated and intimate. In the urban period, however,

Black culture was seized by capitalism and subjected to the impersonal

forces of the market. It is a market over which Black culture artists and

the masses of Black people have had little control.

THE ARTS MOVEMENTS

Music, literature, painting, etc., as we have said, represent the most concentrated forms of cultural expression - the arts. An art movement consists of artists and patrons (supporters) who are united by sharing common interests, themes, and general social rapport. The unity is ideological (how they view the world), political (how they apply these beliefs in analyzing their concrete problems), and sometimes organizational.

Three art movements have emerged among Black people during the urban period that reflect the impact of the changes outlined above. The Harlem Renaissance emerged during the post-migration, post-war period of radical nationalist protest; the WPA (Works Progress Administration) and the Be Bop period developed amidst the revolutionary turbulence of the Great Depression and World War II; and the Black Arts Movement developed on the heels of the Black Power Movement in the 1960s. These powerful cultural arts movements among Black people developed in the context of the most intensive period of Black people's struggle for liberation. How well any particular movement reflected the sentiment and aspirations of the struggling masses must be investigated, however, and not assumed. Let us briefly assess these arts movements by analyzing the concrete conditions in which they emerged, their content and form, and their relationship, appeal, and impact on the masses of Black people.

The 20s: The Harlem Renaissance

The

1920s were prosperous times. After a brief period of postwar decline,

the U.S. economy soared because of the immense profits earned from the

first imperialist war. Black people, as recent arrivals in northern

industrial centers, enjoyed this prosperity as well, though the postwar

riots and numerous lay-offs revealed that the city was not free from

oppression for Blacks.

As

a concept, the "New Negro" accurately sums up what was happening

to Black people. "New" described the migration out of the South,

urbanization of Black people into northern ghettoes, and the

proletarianization of rural southern Black farmers. "New Negro"

also described a wide range of new subjective and ideological

developments. There was greater social class stratification of Black

people. This included the emergence of a new, more assertive middle class

that was critical of the accommodationism of the "old Negro"

(e.g. Booker T. Washington's leadership). With the NAACP, the Urban

League, and the Garvey movement all emerging between 1909 and 1917, there

was the tremendous flowering of the organized struggle of Black people for

liberation.

"New Negro" thus became the credo of the movement of Black writers, artists, musicians, actors, intellectuals, and their patrons which emerged during this period. The cultural expression of this "New Negro" was authentic and widespread. No longer was Black cultural expression isolated and shunned. Artists like Langston Hughes were inspired to expose the life and culture of Black people in a way that had not been done before.

The

Harlem Renaissance was not only a movement of the city, but a particular

city - New York, the country's biggest and most Cosmopolitan city. This

was the first modern art movement of the Afro-American. As such, it had

the major task of defeating the racist notion that Blacks were culturally

inferior. However, the new Black artists, reflecting their middle-class

backgrounds, did not feel bound to the masses in their task of artistic

creativity and production. In this sense, the Harlem Renaissance was petty

bourgeois elitism at its height. On the other hand, the artists had

to face the capitalist market with their work. Publishing companies and

other cultural businesses bought up their products, mass-produced them,

and circulated them. Increasingly, this contradiction between the work of

the artist and the work of the cultural business began to transform Black

art into a more commercial product. The mediating social organization was

the salon gathering of artists and patrons, or the parties

"downtown" frequented by the literary establishment to which

some young Black artists would be invited. In this setting, wealthy

patrons would meet young Black artists whom they would sponsor, thus

providing them with income other than what they were paid from competing

in the market place.

The Harlem Renaissance was the work of a few talented and highly educated Black people, their white publishers and promoters, and a few others who could afford "Black culture." Thus, while it had an impact on this key sector of the Black population, the Harlem Renaissance was practically unknown to the vast majority of Black people and had little direct impact on solving the problems with which they were most concerned.

The 30s and 40s: The WPA Artists and the Be Bop Musicians

The Great Depression laid bare the racist rule of the rich and threw many working people out on the street to starve and die. All working people suffered, but Black people suffered even more because they were the very last hired and the very first fired. This was devastating proof that the North offered no sanctuary from racism and class exploitation. Rather, life in the northern cities merely represented another, perhaps even more vicious manifestation of oppression because it had held out the hope of being different. Black artists were affected as well, since the income derived from selling their art "products" dried up like everything else. This shattered the social organization of the artists that grew up during the Harlem Renaissance. This was not limited to New York, but was spread from coast to coast.Two forces external to the Black community had a tremendous impact on the development of the arts movement of this period. First, the federal government set up an unprecedented welfare program under Franklin D. Roosevelt that included the hiring of artists. Black artists in every part of the country got WPA (Works Progress Administration) jobs. This changed the social relations of cultural production. Before, the artist had worked as an individual, possibly supported by a sponsor, but the key relationship was with a large capitalist firm that took over the commercial aspects of production. Under the WPA, artists began working collectively (often with social scientists), and the government was the employer (actually acting as a large impersonal employer in the name of the entire country). Many people got work, and a lot of work got done.

Second, the overall condition of the masses of people led to a rapid increase in revolutionary political activity, including a significant (at that particular time) role played by the Communist Party, USA. Major developments were the unionization of Black workers into the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations), the organization of the unemployed in the Unemployed Councils, and militant Black-white unity in the Black Belt South (Southern Negro Youth Congress, Southern Tenant Farmers Union, and the Sharecroppers Union). This raised economic and revolutionary change as the fundamental question facing both Blacks and whites. This was a political question that made a profound impact on artists, particularly Black artists. As Richard Wright put it: "Today the question is: Shall Negro writing be for the Negro masses, moulding the lives and consciousness of those masses toward new goals, or shall it continue begging the question of the Negroes' humanity?" The question was answered as the years wore on.

Whereas

Alain Locke could say the the New Negro in the 1920s was "radical on

race matters, conservative on others," Black people in the 1930s and

1940s were increasingly radical on all matters. Black people and

their artists began to understand that racist discrimination was a product

of capitalism and imperialism. They thus became active as leaders and

participants in campaigns for radical and revolutionary changes. These

themes of revolutionary class struggle pervaded the work of many Black

artists. The best examples of this new proletarian consciousness among

Black writers were Richard Wright and Langston Hughes. As cultural

artists, they sought (1) to apply the theory, insights, and lessons of the

world revolutionary struggles to the concrete problems of Black people;

(2) to expose Black people's experiences with racism and poverty in the

United States, and to relate this to the common problem of exploitation

facing the entire working class, thereby developing the cultural basis for

unity of action among Blacks and whites; and (3) to contribute to the

development of a united front of all exploited and oppressed peoples for

the revolutionary overthrow of imperialism as a necessary step in the

total liberation of Black people.

Richard Wright perhaps best summarized this new revolutionary perspective:

|

It means that a Negro writer must learn to view the life of a Negro living in New York's Harlem or Chicago's South Side with the consciousness that one-sixth of the earth surface belongs to the working class. It means that a Negro writer must create in his readers' minds a relationship between a Negro woman hoeing cotton in the South and the men who loll in swivel chairs in Wall Street and take the fruits of her toil. Perspective for Negro writers will come when they have looked and brooded so hard and long upon the harsh lot of their race and compared it with the hopes and struggles of minority peoples everywhere that the cold facts have begun to tell them something. |

Langston

Hughes dramatically spelled out the nature of the revolutionary task of

Black writers in a speech at the First American Writers' Congress in 1935:

|

Negro

writers can seek to unite blacks and whites in our country, not on

the nebulous basis of an interracial meeting, or the shifting sands

of religious brotherhood, but on the solid ground of the

daily working-class struggle to wipe out, now and forever, all the

old inequalities of the past. Negro writers can expose those white labor leaders who keep their unions closed against Negro workers and prevent the betterment of all workers. We

can expose, too, the sick-sweet smile of organized religion - which

lies about what it doesn't know, and about what it does know. And

the half-voodoo, half-clown, face of revivalism, dulling the mind

with the clap of its empty hands. |

And in the world of the performing arts, Paul Robeson, one of the foremost actors and singers of his time, asserted what was in the hearts of many:

| When I sing "Let My People Go," I want it in the future to mean more than it has before. It must express the need for freedom not only of my own race. That's only part of the bigger thing. But of all the working class - here, in America, all over. I was born of them. They are my people. They will know what I mean. |

Unlike

the artists of the Harlem Renaissance who tended to focus on the culture

of the bourgeoisie, the cultural artists of the Depression era were much

more in touch with the sentiment and aspirations of the masses of Black

people. They pointed out that a total restructuring of American society

was necessary if Black people were to be free. They actively lent their

talent and skills to achieve this aim.

| The bebop revolution saw the jazz musician adopting an entirely different social posture...Here, for the first time, a black artistic vanguard assumed whole styles of comportment, attire and speech which were calculated to be the indicia of a group which felt that its own values were more sophisticated than, if not superior to, the mores of the American society at large. The music and the manner developed concomitantly, which indicates that the musicians were aware that each musical innovation was a new way of commenting on the world around them. |

This is true of no one more than the musician Charlie "Bird" Parker, the father of Be Bop:

| Parker spoke through his horn like a man who, after getting along for years on a diet of basic English, had suddenly swallowed the dictionary, yet miraculously managed to digest every page. Where others had played in and around arpeggios on a single chord for four beat, he would involve two, three, or four; where they had given an impression of brisk motion with their little flotillas of eight notes, Parker would play sixteenths. Where tonal discretion had been the better part of their technical valor, Parker threw conventional tonal beauty out of the window to concentrate more fully on matter rather than manner. |

Be Bop improvisation was a cultural parallel to the theory of relativity, and Bird's voice had an impact like the atomic bomb.

The 60s: The Black Arts Movement

The

Civil Rights Movement with its underlying cultural goal of assimilation

was aborted by the reactionary repression Blacks underwent in the form of

assassination, imprisonment, and racist ideological attacks. The Civil

Rights Movement had been the hope of a large and developing number of

aspirants to middle-class life. When it failed, many of these young,

middle-class youths formed the social base for a new nationalist movement

against America. While this had a political aspect, it also had a cultural

aspect. "Black power" became a rallying cry for the newborn

nationalist who began to defect from the Civil Rights Movement,

particularly after the death of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. In

this context the Black Arts Movement was born.

The "Black power" concept and the Black Arts Movement reflected the particular plight of the Black middle class that was previously revealed during the Harlem Renaissance. It desired and had fought for full integration into the "mainstream." But having been barred by pervasive racism, it was forced to become more nationalist and seek its advancement in ambivalent unity with the masses of Black people.

Black

power fell short of pointing out that the problems of Black people

resulted from racist oppression and capitalist exploitation. Similarly,

the Black Arts Movement defined the problems of Black people more as the

result of "European American cultural insensitivity" and not

primarily as the result of the operations of the capitalist system. The

solution proposed by the Black Arts Movement (and Black power) was

essentially reformist: "A cultural revolution in arts and

ideas." This cultural "revolution" was to be rooted in a

new aesthetic, the Black aesthetic. The writer Larry Neat articulated its

purpose:

| The motive behind the Black aesthetic is the destruction of the white thing, the destruction of white ideas, and white ways of looking at the world. The new aesthetic is mostly predicated on an Ethics which asks the question: whose vision of the world is finally more meaningful, ours or the white oppressors? What is truth? Or more precisely, whose truth shall we express, that of the oppressed or of the oppressors? |

Neither the Black Arts Movement nor the Black Power Movement understood, however, that such a cultural revolution was impossible without revolutionary change in the existing capitalist economic and political system. Thus, the Black Arts Movement was more like the Harlem Renaissance than the arts movement of the Depression. In fact, Alain Locke's description of the Renaissance in the 1920s, "radical in form but not in purpose," comes close to an accurate description of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s.

BLACK CULTURE AND IMPERIALISM

It is important to note that as Black cultural expression has increased in quantity and artists have become more expert, there has also been a tremendous increase in the appeal of Black art. The major single feature that has contributed to this dissemination of Black culture in the last fifty years has been, of course, the mass media: advertising, radio, television, film. Through the mass media, the various forms of Black cultural expression become accessible to the broad masses of people, although it is clear that the content of this expression is very tightly controlled by the capitalists owners. Hence, Black cultural expression as it is presented to us today - via theatre, film, music, newspapers, magazines, paperback novels - as popular as it is, is almost entirely devoid of any social content. That is, on the whole, it lacks a concrete analysis of the real content and cause of the problems facing Black people and any orientation toward struggle to change these conditions.

In

order to understand why this is so, it is necessary to understand the

growth of monopoly capitalism and imperialism, and its effect on Black

people and Black culture. "Imperialism and the Black Media"

written by the National Coordinating Committee of the "Year to Pull

the Covers Off Imperialism" Project, outlines the relationship

between monopoly capitalism and the mass media:

| In brief, the pattern of ownership of the mass media is identical to the pattern of monopoly capitalism in the U.S. economy. Ownership is characterized by "media monopolies" and is concentrated among a few large corporations. Heavily represented in the ownership of media are large financial institutions, that serve to bring the mass media under the ownership and control of the same elite U.S. ruling class that owns the rest of the economy. |

A

small ruling class owns almost all of the newspapers, magazines, films,

music, theatres, and radio and TV stations in this country as well as

abroad. As owners, they control the content of what is released in the

media. True, there are occasional exposes or documentaries, but the media

by and large do not present in any meaningful sense the content of the

lives of the masses. The media have performed and continue to perform as

they do because, as stated in "Imperialism and the Black Media,"

| It is not in the interest of U.S. monopoly capitalism and imperialism to allow a true picture of the lives of the masses of people - Black, Asian, Chicano, Native American, Puerto Rican, white - to be presented in this country. Such truth would provide too great a push to the already on-going struggle of the people to end their exploitation and oppression at the hands of U.S. imperialism. |

In

discussing Black culture and the arts, we must remember one thing:

imperialism cannot afford for the cultural lives of the masses of people

to be outside the realm of its control. Hence, we must understand Black

culture and art in two ways: (1) its relationship to the concrete

experiences of the masses of people, which is a history of racist

oppression and exploitation; and (2) the continuous manipulation and

control by capitalists. It is this analysis that can correctly explain in

a comprehensive way the development of the culture of Black people in the

United States and make it a component part of the struggle for liberation.

KEY CONCEPTS

| African cultures (tribal, colonial, national) | Creolization | |

| Art | Cultural imperialism | |

| Be Bop | Culture | |

| Black Arts Movement | Harlem Renaissance | |

| Commercialization | Oral tradition |

STUDY QUESTIONS

1. Discuss the impact of colonialism, imperialism, and racism on the culture of traditional Africa. What are the parallels and contrasts in the development of Afro-American culture?

2.

What is "creolization"? How does it explain the transformation

of Black culture in the United States from African to Afro-American?

Illustrate how this process operated in the United States, and show how

the conditions of slavery influenced the "creolization" process.

3. What social and economic forces shaped Black culture and artistic production during the rural period? the urban industrial period?

4. Discuss the three arts movements (Harlem Renaissance, WPA and Be Bop, and the 1960s Black Arts Movement) that emerged among Afro-American people in the urban period.

SUPPLEMENTARY READINGS

1. Houston A. Baker, Jr., The Journey Back: Issues in Black Literary Criticism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

2.

William Ferris, ed., Afro-American Folk Art and Crafts. Boston: G.

K. Hall, 1983.

4. Samella Lewis, Art: African American. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1978.

5. Eileen Southern, The Music of Black Americans: A History. New York: W. W. Norton, 1971.