|

Peonage

. . . was defined thus by a judge: "It is where a man in

consideration of an advance or debt or contract, says, 'Here, take me,

I will give you dominion over my person and liberty, and you can work

me against my will hereafter, and force me by imprisonment, or threats

of duress to work for you until that debt or obligation is

paid.'" Experience has shown, too, that the judge might have

added, "Until I, the planter, shall say that the debt has been

paid." Carter G. Woodson, The Rural Negro, 1930

|

The

end of the slave period was followed by a period in which the experiences of

Black people were both similar to and different from what they had been. The

Civil War and the Reconstruction were the years of emancipation. It was a

period of transition in which great social, political, and economic upheaval

destroyed some aspects of slavery but allowed other aspects to continue (not

entirely in form, but in essence).

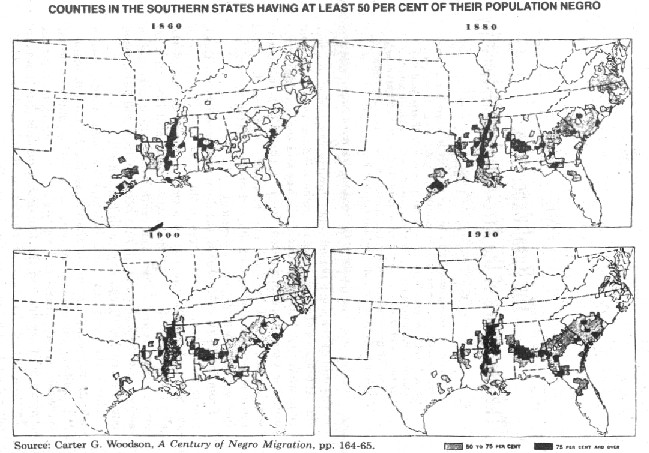

From

the 1870s to the 1930s, the dominant experience of Black people in the

United States was in the rural Black Belt area of the South. In 1890, a

quarter of a century after the end of the Civil War, four out of every five

Black people still lived in rural areas of the United States. Ten years

later in 1900, nine out of every ten were in the South. And between 1890 and

1910, three out of every five Blacks worked in agriculture.

This is the period in which Black people were molded into a definite nationality, a people sharing social, cultural, economic, and political experiences, as well as suffering under a brutal system of social control and repression. Of course the common experience of slavery laid the foundation for this, but it was in the rural period that the full expression of this national development and national oppression took place. It is necessary to emphasize that this development was stunted because of repression and social control.

Our focus here is, not on the chronological history of this period, but rather is to analyze the major aspects of the social content of this experience.

TENANT

FARMING

The

most basic aspect of a people's experience is the way they produce and

consume whatever is necessary in order to survive, or in other words,

their economic life. In the rural experience Black people were

"apparently" free, but they continued to be oppressed by an

economic system that compelled them to work in virtual bondage. The

mechanism by which Black people were kept in servitude was the tenant

system.

In theory, the tenant system was simply a contractual arrangement by which a landowner would exchange the use of land and perhaps tools, seed, and "furnishings" for either cash or a share of the profits and/or produce (crops). Charles S. Johnson, Edwin Embree, and Will Alexander describe this system more fully:

| Tenants may be divided into three main classes: (a) renters who hire land for a fixed rental to be paid either in cash or its equivalent in crop values; (b) share tenants, who furnish their own farm equipment and work animals and obtain use of land by agreeing to pay a fixed per cent of the cash crop which they raise; (c) share-croppers who have to have furnished to them not only the land but also farm tools and animals, fertilizer, and often even the food they consume, and who in return pay a larger per cent of the crop. |

Table

7 (below) outlines the typical arrangements for each type of tenancy.

At

this level, such an economic arrangement appears to be a free exchange in

which the economic partners have the freedom to enter on arrangement or to

leave it. As has been pointed out, "Normally it is regarded as a step

on the road to independent ownership." However, this was not the

situation in the South where traditions and practices ensured

exploitation. Emerging from a legacy of slavery, the economic partners

were quite unequal. Rather than being partners, they can more correctly be

defined as the oppressor and the oppressed.

In

the first place, the overwhelming numbers of Blacks were sharecroppers and

not renters or even share tenants. Moreover, Black farmers/workers were

usually illiterate, had very limited experience in making contracts, and

were very dependent upon the landowner for credit to survive from crop to

crop.

Analyzing the tenancy system in the 1930s, Johnson, Embree,

and Alexander wrote:

| It is to the advantage of the owner to encourage the most dependent form of share cropping as a source of largest profits...landlords, thus, are most concerned with maintaining the system that furnishes them labor and that keeps this labor under their control....The means by which landowners do this are: first, the credit system; and second, the established social customs of the plantation order. |

Table 7

TENANCY

| TYPES OF TENANCY | ||

| Share Cropping for Half and Half | Share Renting for Third and Fourth | Cash or Standing Renting |

| LANDLORD FURNISHES | ||

| Land House Fuel Tools Work Stock Feed for Stock Sees One half of Fertilizers |

Land House fuel One fourth or one third of Fertilizers |

Land House Fuel |

| TENANT FURNISHES | ||

| Labor One half of Fertilizers |

Labor Work Stock Food for Stock Tools Seed Three fourths or two thirds of Fertilizers |

Labor Work Stock Food for Stock Tools Seed Fertilizers |

| LANDLORD GETS | ||

| One half of crop | One fourth of crop or one third of crop | fixed amount in cash or cotton |

| TENANT GETS | ||

| One half of crop | Three fourths or two thirds of crop | entire crop less fixed amount |

They go on to describe the way the system functioned to keep Blacks indebted:

|

As a part of the age-old custom in the South, the landlord keeps the books and handles the sale of all the crops. The owner returns to the cropper only what is left over of his share of the profits after deductions for all items which the landlord has advanced to him during the year: seed, fertilizer, working equipment, and food supplies, plus interest on all this indebtedness, plus a theoretical "cost of supervision." The landlord often supplies the food - "pantry supplies" or "furnish" - and other current necessities through his own store or commissary. Fancy prices at the commissary, exorbitant interest, and careless or manipulated accounts, make it easy for the owner to keep his tenants constantly in debt. |

The

landowner was -able to manipulate the farmer so that the initial credit

extended to the farmer nearly always resulted in the farmer's going

further and further into debt. The landowners also manipulated the law to

enact "measures which compelled the employee to remain in the service

of his employer." Indebtedness thus became the basis of what turned

out to be forced labor, or what is called peonage.

PEONAGE

Carter Woodson described in his 1930 study how the tenancy system gave rise to peonage:

| Peonage developed as a most natural consequence of things in the agricultural South. The large planters constitute a borrowing class. It is customary for financial institutions to advance for a year sufficient money to cover the expenses of the landlord and his tenants, the amount being determined on the basis of one tenant for each twenty acres. The landlord, then, must hold his tenants by fair or foul means. If they desert him he is bankrupt. Authority, therefore, must be maintained with overseers using whips and guns to strike terror to the tenants who are kept down in the most debased condition. Negro women are prostituted to the white "owners" and drivers; and children are permitted to grow up in ignorance with no preparation for anything but licentiousness and crime. |

Often

landowners or their agents would go from town to town hiring farm laborers

with the Understanding that they would pay them wages and advance them

provisions from the "company store." Woodson recounted an

investigator's report of what would then befall them:

| "The laborers arrive and at the outset are indebted to the employer, who sees that they trade out their wages at the commissary, and in many instances, by a system of deductions and false entries, manages to keep the laborer perpetually in debt. If the laborer hap, a family, so much the better for the employer; they must live out of the commissary and if the laborer runs away his family are detained at the camp. To enforce the payment of such debts young children have been withheld from their parents. If the victim escapes the law is invoked. He is arrested under false pretenses, cheating, swindling, and false promises. There is usually no actual trial. The arresting officer in collusion with the planter induces the victim to return to work rather than go to jail," and "so he returns to bondage with a heavier load of debt to carry, for the cost of pursuit and arrest is charged to him. Often no process is issued for arrest, but the employer arrests without process, returns the prisoner to his labor camp and inflicts severe chastisement. Many of the labor contracts contain provisions to the effect that the laborer consents to allow himself to be locked in a stockade at night and at any other time when the employer sees fit to do thus." |

Peonage

in its most extreme form could be seen in the chain gang. Woodson

described the process:

| The unusual prosperity of the country and, of course, of the South, necessitated a large labor force. To supply this need it became customary to fall back on convict labor. The first step in such peonage was the "benevolent" practice of the white men who would volunteer to pay the fines of Negroes convicted of minor crimes, and thus get them out of jail. The next step was to assure, by physical restraint, the working out of the debts thus incurred. Finally came the cooperation of justices, constables, and other officials in providing a supply of this forced labor by "law." |

Though

peonage may not have been practiced by the majority, it did exist in areas

of Mississippi, Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina where rich planters

had the political and social wherewithal to enforce it.

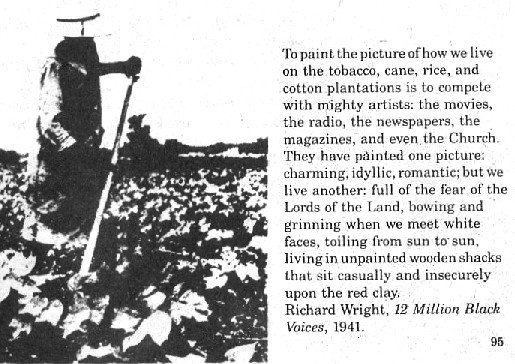

Describing the conditions of the Black agricultural experience, Johnson, Embree, and Alexander wrote in the 1930s:

| For many years, even after Emancipation, black tenants were the rule in the cotton fields and the determination to "keep the Negro in his place" was, if anything, stronger after the Civil War than before.... the old "boss and black" attitude still pervades the whole system. Because of his economic condition, and because of his race, color, and previous condition of servitude, the rural Negro is helpless before the white master. Every kind of exploitation and abuse is permitted because of the old caste prejudice. |

The other side of the rural experience was that it did enable Black people to own some things, while in the slave period they were virtually propertyless. Moreover, while rural farmers didn't own much, they at least had the possibility of getting out of debt, purchasing a few pieces of farm equipment a little land, and a decent house, and even saving money. Thus, while the rural tenancy experience was in the main one of forced labor based on indebtedness (and in its most severe form, peonage), there was also a "middle-class" aspect to it that makes these people quite different from the wage worker in the industrial city. Farmers were poor, but they were usually in day-to-day managerial control of their farm lands, even if they were only sharecropping. This control was the crucial factor in making the farming experience "middle class" in that authority and control of work is a middle-class experience,

Black

tenants had two choices, to go into debt or to increase their property

holdings. To the extent that the tenant sank into debt, the life of a

tenant took on the character of a modern worker using land and tools owned

by someone else to make a living. On the other hand, to the extent that

the tenant was successful and was able to buy land, equipment, and

livestock, life became more secure and independent. This type of self-employment

is one of the traditional bases for the middle class in a capitalist

society. Of course all of this was controlled by the repression of the

southern culture of white supremacy and by the terror of the lynch mob.

The general pattern was for the tenant to go into debt, but aspire to

success. Therefore, while their objective conditions were approximating an

agricultural working class, their consciousness held out for a

middle-class type of life.

THE

CHURCH

As

will be more fully described in a later chapter, the rural experience was

the historical period in which the social and cultural organization of

Black people was developed. This must be viewed in relationship to the

economic character of the Black Belt, and to the forms and methods of

social control and violent repression experienced by Black people. During

the rural period the development of the Black church remained the major

factor in the overall development of the Black community. The church was

the central social- institution in which all forms of social life were

organized and regulated. This included moral and social codes

for family life, recreational behavior, orientations towards the problems

faced by Black people, and the solutions to those problems. This is both

to the credit and discredit of the church, because while objectively it

is what held Black social life together, it was most often held together

for survival rather than forms of active resistance for positive social

change (though positive changes were made in some cases). Hence, the

church was simultaneously the social basis for two kinds of leadership:

militancy and "uncle tomism."

DISFRANCHISEMENT AND SOCIAL REPRESSION

Under slavery the social control of Black people was total and was fully reinforced by all levels of law, from the federal government to the smallest county or town government in the South. The Civil War resulted in the emancipation of the slaves, and new federal legislation was passed giving Black people the right to vote. This newly acquired political enfranchisement was short-lived however. Robert Allen provides some of the reasons for this:

|

Black

Reconstruction was made possible because Northern businessmen and

politicians supported enfranchising the ex-slaves. This, however,

was an alliance of convenience in which the businessmen and

politicians used black people as pawns in their attempt to

consolidate the economic and political control of the white North

over the white South. Black men were given the vote, not so much out

of sense of racial justice as to offset the political power of the

white South. After all, the North had won the war and Northern

leaders were anxious to ensure that their national political

hegemony was firmly established. They believed this could be

accomplished by allowing the freedmen to exercise the franchise

within the framework of the Republican Party. After about ten years,

when the North was well on the road to achieving economic

penetration of the South, black people were abandoned by their

so-called friends. |

Once northerners secured their economic and political dominance of the South, they left white Southerners alone to deal with Blacks.

From at least 1890 onward, Black disfranchisement was a leading issue, and it helped reunite the white South, which had been divided over the agrarian reform movement that pitted poor whites against wealthy landowners and industrialists. "'Political niggerism," as Paul Lewinson said, "was an issue on which the vast majority of Southerners thought alike." There were two problems, however. One, the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution specifically stated that the right to vote could not be denied "on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. Two, any scheme to disfranchise Blacks had to be carefully formulated so that whites would not also be excluded.

The

devices for the political disfranchisement of Black people were soon

developed. Lewinson describes the new tactics that were instituted

throughout the South:

| They

perpetuated, in the first place, certain devices of the statutory

election codes: A poll tax or other taxes must be paid by the

applicant for registration. Registration was to take place months in

advance of polling time, and a receipt for taxes paid must be shown

to either registration or election officials, or to both. It was

left to the officials, actually though not necessarily in law, to

ask for these receipts, so that the Negro voter, unused to

preserving documents, could often be disfranchised through sheer

carelessness on his part.

Among the new features introduced was the property qualification. This ran to two or three hundred dollars. One or more alternative qualifications might be offered by the would-be voter. Crude literacy - reading and writing - was one. Another was a sort of civic "understanding," tested by the ability to interpret the State or Federal constitution to the satisfaction of the election officer. "Good character" might also qualify, when supported by sworn testimonials, or by evidence of steady employment during a specified preceding period, or by an affidavit giving the names of employers for a period varying from three to five years. The property and literacy qualifications cut out large numbers of Negroes automatically; the alternatives could easily be manipulated by the officers in charge. In addition, residence requirements were greatly extended throughout the Southern States, and the list of crimes involving disfranchisement diversified until it included petty larceny, wife beating, and similar offenses peculiar to the Negro's low economic and social status. To, safeguard whites of low intelligence or small property, the so-called "grandfather clauses" were devised. For a period of years after the adoption of the respective constitutions, permanent registration without tax or other prerequisites was secured either to persons who had the vote prior to 1861 and their descendants; or to persons who had served in the Federal or Confederate Armies or in the State militias and to their descendants. This exemption from tests obviously ran only for whites. |

The poll tax, property qualifications, literacy and civic tests, good character and residency requirements, disqualifications for petty crimes, and the grandfather clauses effectively blocked the possibility of Blacks' engaging in electoral politics.

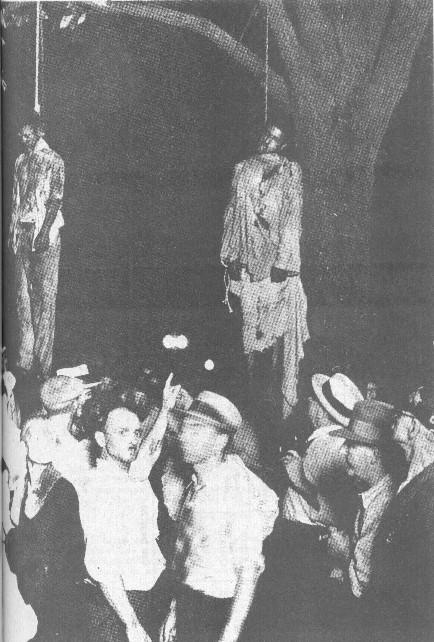

The social repression of Black people took on further ominous overtones with the violent genocidal practice of lynching. Table 8 provides data on the incidences of lynching. These data, of course, only give a glimmering of an idea of the extent to which Blacks were lynched since their lynchings often went unrecorded.

Moreover,

most data on lynchings were based on a fairly limited definition of

lynching:

| Any assemblage of three or more persons which shall exercise or attempt to exercise by physical violence and without authority of law any power of correction or punishing over any citizen or citizens or other person or persons in the custody of any peace officer or suspected of, charged with, or convicted of the commission of any offense, with the purpose or consequence of preventing the apprehension or trial or punishment by law of such citizen or citizens, person or persons, shall constitute a 'mob' within the meaning of this Act. Any such violence by a mob which results in the death or maiming of the victim or victims thereof shall constitute 'lynching' within the meaning of this Act: Provided, however, That 'lynching' shall not be deemed to include violence occurring between members of groups of lawbreakers such as are commonly designated as gangsters or racketeers, nor violence occurring during the course of picketing or boycotting or any incident in connection with any 'labor dispute'... |

Many were lynched under circumstances not covered by this definition. The Commission on Interracial Cooperation in 1942 pointed to two cases highlighting the complications of defining lynching:

|

A

man is out fishing. He discovers a body on the bank of a creek. It

is clearly evident that the man was murdered. Maybe his body is

riddled with bullets - his feet wired together, his hands

tied behind him, his head bashed in. There have been no reports of

any trouble in the county. Was he lynched or was he murdered? |

Table

8

LYNCHINGS OF WHITES AND BLACKS, 1882-1946

| Period | Whites | Blacks | Total |

| 1937-1946 | 2 | 42 | 44 |

| 1927-1936 | 14 | 136 | 150 |

| 1917-1926 | 44 | 419 | 463 |

| 1907-1916 | 62 | 608 | 670 |

| 1897-1906 | 146 | 884 | 1,030 |

| 1887-1896 | 548 | 1,035 | 1,583 |

| 1882-1886* | 475 | 301 | 776 |

| Totals ...... | 1,291 | 3,425 | 4,716 |

*

Indicates 5 year period. The other intervals are 10 year periods.

Source : Based n Jessie P. Guzman and W. Hardin Huges, Negro Year Book,

p.307

As

vague as the definitions may have been, it was clear to Black people that

they lived under the constant threat of being killed.

Lynching

was not only a specific method of murdering particular individuals, but

also was the basis for developing a pervasive climate of terror and fear

that became the cornerstone of the southern way of life. The logic was

clear: Black people would be afraid of being lynched and therefore would

observe the code of conduct informally prescribed by the dictates of white

supremacy.

ORGANIZED

RESISTANCE

In all societies in all stages of history, where there is oppression there is resistance. Black people were not completely docile; they found many ways to resist and rebel. Throughout the Black Belt South individuals and families have resisted attacks, in some cases in courageous armed confrontation with lynch mobs. However, more significant than this is the pattern of collective resistance.

The Messenger recognized the importance of collective resistance in its 1919 proposal to resist lynching, which it saw as the "arch crime of America." It proposed two methods of resistance. The first was the use of physical force:

|

We

are consequently urging Negroes and other oppressed groups

confronted with lynching or mob violence to act upon the recognized

and accepted law of self-defense. Always regard your own life as

more important than the life of the person about to take yours, and

if a choice has to be made between the sacrifice of your life and

the loss of the lyncher's life, choose to preserve your own and to

destroy that of the lynching mob.... The

Messenger wants to explain the reason why Negroes can stop lynching

in the South with shot and shell and fire...A mob of a thousand men knows it can beat down fifty Negroes, but when those

fifty Negroes rain fire and shot and shell over the thousand, the

whole group of cowards will be put to flight... The appeal to the conscience of the South has been long and futile, its soul has been petrified and permeated with wickedness, injustice and lawlessness. The black man has no rights which will be respected unless the black man enforces that respect.... In so doing, we don't assume any role of anarchy, nor any shadow of lawlessness. We are acting strictly within the pale of the law and in a manner recognized as law abiding by every civilized nation. We are trying to enforce the laws which American Huns are trampling in the dust, connived in and winked at by nearly all of the American officials,, from the President of the United States down... Whenever

you hear talk of lynching, a few hundred of you must assemble

rapidly and let the authorities know that you propose to have them

abide by the law and not violate it... Ask the Governor or the

authorities to supply you with additional arms and under no

circumstances should you Southern Negroes surrender your arms for

lynching mobs to come in and have sway. To organize your work a

little more effectively, get in touch with all of the Negroes who

were in the draft. Form little voluntary companies which may quickly

be assembled. Find Negro officers who will look after their

direction...When this is done, nobody will have to sacrifice his

life or that of anybody else because nobody is going to be found

who will try to overcome that force. |

The second form of resistance that The Messenger proposed was

economic force:

|

Now

one of the best ways to strike

a man is to strike him in the pocketbook...Negroes are the

chief producers of cotton. They also constitute a big factor in the

South in the production of turpentine, tar, lumber, coal and iron,

transportation facilities and all agricultural produce. They should

be thoroughly organized into unions, whereupon they could make

demands and withhold their labor from the transportation industry

and also from personal and domestic service and the South will be

paralyzed industrially and in commercial consternation... |

While The Messenger's program of physical and economic resistance was a specific response to lynching, organized resistance to economic oppression had been going on for some time even though it was plagued with problems.

In

the aftermath of Reconstruction and as a reaction to the Depression of

1873, which was particularly hard on the agrarian South, white farmers had

organized the Southern Alliance of Farmers. Theoretically, the material

basis for an alliance was there. Though Blacks faced greater economic

hardship, both Blacks and poor white farmers suffered under the tenant

system.

But

as Robert Allen points out, the alliance between the two groups had been

thwarted in the antebellum period:

| Although there was much to recommend an alliance between black and white farmers, several historical factors had contributed to a deep rift between the two groups. In the first place, many of the poor white farmers were hostile towards blacks, tending to regard them as economic enemies. The explosive advance of the cotton plantation system in the decades prior to the Civil War had seriously undermined the independent small farmers. Unable to compete with the large planters in cotton production they were inexorably pushed out of the fertile regions or forced to emigrate to the frontier. Many of these ousted farmers became the "poor, white trash," "hillbillies," and "crackers" of the mountains and other inhospitable regions of the South. The class of poor rural whites was thereby swelled by the growth of the slave plantation system. However, in the hysterical racist atmosphere cultivated by the big planters, the poor whites were prone to identify their distress not with the slave system but with the slaves themselves. The unquestioning acceptance of white supremacy demanded by the planters and their allies combined with the formers' custom of employing poor whites as harsh overseers between master and slave contributed immensely to racial antagonisms. The historic hostility between impoverished rural white and black populations thus has roots that reach back into the antebellum period. |

This

"historic hostility" continued to obstruct any possibility for

an alliance, even during the late 1800s when economic conditions worsened

for both. Allen pinpoints the reasons for the failure of the two groups to

ally:

| [H]istorically, two contradictory dynamics were at work among the white farmers of the late nineteenth century, one pushing them toward economic and political alliance with similarly exploited-black farmers, and the second, based on white supremacy, moving them to economic and political hostility toward black farmers. |

Despite

this hostility, the whites who had formed the Southern Alliance and had

excluded Black members realized they needed the support of Black farm

workers. They thus helped organize a separate Black organization, the

Colored Farmers' National Alliance and Cooperative Union.

Some

historians have contended that the Colored Alliance

"was little more than an appendage" to the Southern

Alliance, but there were differences in their approaches. In 1891, the

Colored Alliance began working on a plan for Black cotton pickers to

strike for higher wages. The president of the Southern

Alliance reacted by declaring that Blacks were trying "to

better their conditions at the expense of their white brethren." The

white Alliance was not about to support any radical action that would

threaten the interests of white farmers, and it consistently undermined

Black efforts to act independently. As Allen points out:

| Underlying this dispute

was a difference in class interest between the two groups. Many of

the white farmers, especially the leaders of the agrarian revolt

were farm owners and their ideology tended to be that of a

landowning class. Between white and black farmers, who were

overwhelmingly sharecroppers differing only in degree from

landless farm workers, there was a smoldering class conflict not

altogether unlike the contemporary conflict between farm owners and

farm workers...

Black farmers thus were caught in a position of economic and racial conflict with white farmers and their political representatives. However... the black farmers lacked a truly independent organization through which they could develop and articulate their own program. Instead they were reduced to subservient status in the agrarian reform movement. |

Although

the Colored Farmers' National Alliance and Cooperative Union built up a

membership of over one million Black farmers, its fate was set by the

betrayal of white farm leadership.

Later, a more revolutionary approach was undertaken by organizations like the Southern Farm Tenant Union and the Sharecroppers Union, most active in the 1930s and 1940s. The organizations built a membership of Black and white farmers, and were militant enough to even engage in armed struggle to protect its membership from the "southern justice" of sheriffs and lynch mobs.

THE

DECLINE OF RURAL LIFE: OUTMIGRATION

In

the end, the overall dynamic character of industrial capitalism

significantly reduced the demand for agricultural labor and increased

the demand for industrial labor. The boll weevil that invaded the South

during the 1920s and 1930s and led to the deflation of land values helped

speed the process of agricultural decline. Particularly during World Wars

I and II when the war industries were at their peak, Black people left the

South and headed North. This exodus is one of the major social disruptions

of Black social life, in many ways equal to the Civil War and

Reconstruction.

|

|

||

|

|

KEY CONCEPTS

| Alliance of farmers (white vs. Black) | Lynching | |

| Black Belt | Peonage/Indebtedness | |

| Disfranchisement | Resistance (physical force vs. economic force) | |

| Emancipation experience (Civil War vs. Reconstruction) | Sharecropping | |

| Farming/Agriculture | Tenancy |

STUDY QUESTIONS

1. What are the different forms of tenancy? Describe the relationship between each type of tenant and the landowner.

2. Compare peonage to the middle-class aspects of tenant farming.

3. What political and violent methods were used to control and repress Black people during the rural period? Compare these methods with those that were used during slavery.

4. How did Black people organize resistance to fight against exploitation and repression during the rural period?

SUPPLEMENTARY READINGS

1. Leon F. Litwack, Been in the Storm so Long. The Aftermath of Slavery. New York: Random House, 1979.

2. Edward Magdol, A Right to the Land: Essays on the Freedmen's Community. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1977.

3.

Jay R. Mandle, The Roots Of Black Poverty.- The Southern Plantation

Economy after the Civil War. Durham: Duke Uni- versity Press, 1978.

4. Roger L. Ransom and Richard Sutch, One Kind of Freedom: The Economic Consequences of Emancipation. New York: Cam- bridge University Press, 1977'

5. Theodore Rosengarten, All God's Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975.