|

The white man turned

...... I'm from

up North," he said.... "They need men up there - good men

- all they can get. If Big Mat speaks for this family tell him they

can use him and all the other able menfolks in his house:' . .

. William Attaway, Blood on the Forge, 1941.

|

|

Lucille

and I both met our Waterloo in the following fashion. I had cooked a

huge dinner for many guests - we always had company besides the

ordinary family of five - and it was 9:00 P.M. before we two sat

down to our meal, both too tired to eat. Suddenly

the bell rang furiously and Lucille came back, flushed with anger.

"She say to put the cake right on the ice!" Soon

the bell rang again. "Is that cake on the ice?" called out

Mrs. B - I

sang out. "We've just started our dinner, Mrs. B - Later I said

to Lucille: "Does she think we're horses or dogs that we can

eat in five minutes - either a coltie or a Kiltie?" (Kiltie was

the d6g.) Lucille, who loved such infantile jokes, broke into peals

of laughter. In

a second Mrs. B - - was at our side, very angry. She had been

eaves-dropping in the pantry. "I heard every word you

said!" "Well,

Mrs. B - - we're not horses

or dogs, and we have been e4fing only five minutes!" "You've

been a disturbing influence in this house ever since you've been

here!" Mrs. B - - thundered. "Before you came Lucille

thought I was a wonderful woman to work for - and tonight you may

take your wages and go. Tomorrow, Lucille, your aunt is to come, and

we shall see whether you go too!" . . . Jobless,

and with only $15 between us and starvation, I still felt a wild

sense of joy. For just a few days I should be free and self-

respecting! ... Naomi

Ward, "I Am a Domestic," 1940. |

Black people had the opportunity to begin moving out of the South in large numbers and they did. They moved to the cities of the North and the South, but particularly important was the move out of the South, and eventually to the cities of the West. The great migrations occurred during the two world wars when there was a great demand for unskilled labor in northern industries. Harold Baron captures the essence of what took place during this period:

| This new demand for black workers was to set in motion three key developments: first, the dispersion of black people out of the South into Northern urban centers; second, the formation of a distinct black proletariat in the urban centers at the very heart of the corporate-capitalist process of production; third, the break-up of tenancy agriculture in the South. World War II was to repeat the process in a magnified form and to place the stamp of irreversibility upon it. |

THE

URBANIZATION OF BLACKS

Between

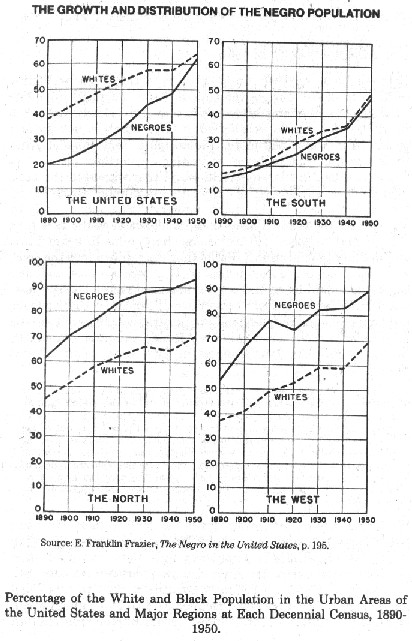

1910 and 1940, the proportion of the Black population residing in urban

areas of the United States increased from 28% to 48.2% (side diagrams

below). When the census was first taken in 1790, Black people were found

in large numbers in only four cities: New York, Baltimore, Philadelphia,

and Boston. After Emancipation, Blacks began migrating to northern as well

as southern cities, but it was World War I that witnessed the mass

migrations to northern cities. "Hostilities in Europe," wrote

Baron, "placed limitations on American industry's usual labor supply by

shutting off the flow of [European] immigration at the very time the

demand for labor was increasing sharply due to a war boom and military

mobilization." Blacks thus were drawn into the steel, meat-packing, and

auto industries, of northern cities and into shipbuilding and heavy

industry of southern cities. Though post- war demobilization brought heavy

unemployment for Black people, a strong economic recovery and very

restrictive immigration laws in the early 1920s encouraged a second

migration out of the South. E. Franklin Frazier notes in The Negro in the

United States:

| During and following the War there was a great demand for unskilled labor to fill the gap created when immigrants returned to Europe and immigration from Europe ceased. At the same time economic conditions in the South growing out of the tenancy system tended to "push" the Negro out of the South. During 1915 and 1916, crop failures, floods, and the ravages of the boll weevil resulted in the widespread disorganization of the plantation economy. In a study which was designed to measure the relative strength of the "pull" of northern industries and the "push" of southern agriculture, Lewis concluded that the "pull" of the North was primarily responsible for the migrations. |

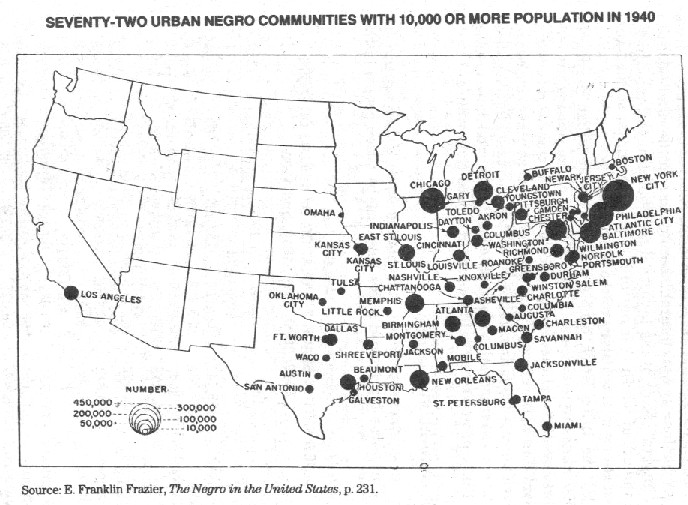

World

War I I gave further impetus to the "pull" of northern

cities (see Figures D and E and Table 9 below). During and following World

War II, Blacks for the first time were drawn in large numbers to the west

coast where defense industries were located.

In 1950, only 40% of the Black population lived on farms and the number of acres operated declined 37% to 25.7 million acres. Moreover, in 1950 the United States Census Bureau reported that for the "nonwhite" population - 95% of which was Black - only 18.4% were employed as farm workers, with 38% as "blue collar workers" (mainly industrial) and 34% as "service workers." This transformation of the social form of the Black community - from a pre dominantly agricultural laboring class in the rural South to an integral sector of the industrial proletariat more concentrated in the urban North - is one of the most significant social tranformations in the history of the United States.

By

the 1970s Black people had become an urban people. In 1890 whites were

twice as likely to be in cities, passing the 50% mark by 1920. However,

the World War I and World War II migrations to the city by Black people,

as well as other subsequent developments (sub urbanization of whites,

increased fertility/birth rates and lower mortality/death -rate for

Blacks, etc.), have resulted in Black people today being more urbanized

than whites.

THE

"NEW NEGRO"

This

new urban experience, in combination with their experience in World War I,

produced a new response by Black people in the

| CITY | 1940 | 1930 | 1920 | 1910 | 1900 |

| ( NORTH ) | |||||

| New York | 458,444 | 91,709 | 60,666 | ||

| Chicago | 277,731 | 44,103 | 30,150 | ||

| Philadelphia | 250,880 | 84,459 | 60,613 | ||

| Detroit | 149,119 | 5,741 | 4,111 | ||

| Washington | 187,266 | 94,446 | 86,702 | ||

| Baltimore | 165,843 | 84,749 | 79,258 | ||

| St. Louis | 108,765 | 43,960 | 35,516 | ||

| New Orleans | 149,034 | 89,262 | 77,714 | ||

| Memphis | 121,498 | 52,441 | 49,910 | ||

| Birmingham | 108,938 | 52,305 | 16,575 | ||

| Atlanta | 104,533 | 51,902 | 35,729 | ||

Source:

E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro in the United States, p. 230.

There was a new confidence and determination, which can be seen in this

editorial W. E. B. DuBois wrote for The Crisis in 1919:

|

We

return from the slavery -of uniform which the world's madness

demanded us to don to the freedom of civil garb. We stand again to

look America squarely in the face and call a spade a spade. We sing:

This country of ours, despite all its better souls have done and

dreamed, is yet a shameful land. It

has organized a nationwide and latterly a worldwide propaganda of

deliberate and continuous insult and defamation of black blood

wherever found. It decrees that it shall not be possible in travel

nor residence, work nor play, education nor instruction for a black

man to exist without tacit or open acknowledgment of his inferiority

to the dirtiest white dog. And it looks upon any attempt to question

or even discuss this dogma as arrogance, unwarranted assumption and

treason. This

is the country to which we Soldiers of Democracy return. This is the

fatherland for which we fought! ... But by the God of Heaven, we are

cowards and jackasses if now that that war is over, we do not

marshal every ounce of our brain and, brawn to fight a stern",

longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own

Ian We

return.

|

A new term developed for this confident and determined Black - the "New Negro."

|

In

politics, the New Negro, unlike the Old Negro, cannot be lulled into

a false sense of security with political spoils and patronage. A job

is not the price of his vote. He will not continue to accept

political provisory notes from a political debtor, who has already

had the power, but who has refused to satisfy his political

obligations. The New Negro demands political equality. He recognizes

the necessity of selective as well as elective representation. He

realizes that so long as the Negro votes for the Republican or

Democratic party, he will have only the right and privilege to elect

but not to select his representatives. And he who selects the

representatives controls the representatives. The New Negro stands

for universal suffrage. A

word about the economic aims of the New Negro. Here, as a worker, he

demands the full product of his toll. His immediate aim is more

wages, shorter hours and better working conditions. As a consumer,

he seeks to buy in the market, commodities at the lowest possible

price. The

social aims of the New Negro are decidedly different from those of

the Old Negro. Here he stands for absolute and unequivocal "social

equality." He realizes that there cannot be any qualified

equality. He insists that a society which is based upon justice can

only be a society composed of social equals. He insists upon

identity of social treatment. It went on to specify the methods for achieving these goals: First,

the methods by which the New Negro expects to realize his political

aims are radical. He would repudiate and discard both of the old

parties - Republican and Democratic. His knowledge of political

science enables him to see that a political organization must have

an economic foundation. A party whose money comes from working

people, must and will represent working people. Now, everybody

concedes that the Negro is essentially a worker. There are no big

capitalists among them. There are a few petit bourgeoisie, but the

process of money concentration is destined to weed them out and drop

them down into the ranks of the working class. In fact, the

interests of all Negroes are tied up with the workers. Therefore,

the Negro should support a working class political party. He is a

fool or insane, who opposes his best interests by supporting his

enemy. As workers, Negroes have nothing in common with their

employers. The Negro wants high wages; the employer wants to pay low

wages. The Negro wants to work short hours; the employer wants to

work him long hours. Since this is true, it follows as a logical

corollary that the Negro should not support the party of the

employing class. Now, it is a question of fact that the Republican

and Democratic Parties are parties of the employing or capitalist

class. On

the economic field, the New Negro advocates that the Negro join the

labor unions. Wherever white unions discriminate against the Negro

worker, then the only sensible thing to do is to form independent

unions to fight both the white capitalists for more wages and

shorter hours, on the one hand, and white labor unions for justice,

on the other, It is folly for the Negro to fight labor organization

because some white unions ignorantly ignore or oppose him. It is

about as logical and wise as to repudiate and condemn writing on the

ground that it is used by some crooks for forgery. |

Most

of this energy was generated in and focused on the urban environment -

with mixed results, as will be seen later in the chapter.

THE

PROLETARIANIZATION OF BLACKS

The

urban experience for Black people was similar to that of any other

formerly rural and poor people. The city was a relatively small place

where large numbers of people lived and therefore social and cultural

activities were intensified. Moreover, the economic basis for all of this

was significantly different from the rural experience.

Black

people were transformed into wage workers with little opportunity to be

self-employed or to own the means of making a living (like a piece of

land) in an independent way. In the city virtually everyone worked for

someone else. Unlike white workers, however, Blacks in the city were the

"last hired and the first fired" so that the vicious pattern of

rural discrimination persisted in a new form in the urban environment.

Initially, there continued to be jobs that were occupied by Black people only. As Harold Baron has pointed out :

| In industry generally the black worker was almost always deployed in job categories that effectively became designated as "Negro jobs.". . . The superintendent of a Kentucky plough factory expressed the Southern view: "Negroes do work white men won't do, such as common labor; heavy, hot, and dirty work; pouring crucibles; work in the grinding room; and so on. Negroes are employed because they are cheaper. . . . The Negro does a different grade of work and makes about $.10 an hour less." There was not a lot of contrast in the words of coke works foremen at a Pennsylvania steel mill: "They are well fitted for this hot work, and we keep them because we appreciate this ability in them.". "The door machines and the jam cutting are the most undesirable; it is hard to get white men to do this kind of work." |

|

In

the North there was some blurring of racial distinctions, but they

remained strong enough to get the black labor force off quite

clearly. While the pay for the same job in the same plant was

usually equivalent, when blacks came to predominate in a specific

job classification, the rate on it would tend to lag. White and

black workers were often hired in at the same low job

classification; however for the whites advancement was often

possible, while the blacks soon bumped into a job ceiling. In terms

of day-to-day work, white labor was given a systematic advantage

over black labor and a stake in the racist practices.... |

|

....the

bulk of the Negro population became concentrated in the lower- paid,

menial, hazardous, and relatively unpleasant jobs. The employment

policy of individual firms, trade-union restrictions, and racial

discrimination in training and promotion made it exceedingly

difficult for them to secure employment in the skilled trades, in

clerical or sales work, and as foremen and managers. Certain entire

industries had a "lily-white" policy - notably the public

utilities, the electrical manufacturing industry, and the city's

banks and offices. Ira De A. Reid, who was on the Social Security Board, further detailed the plight of Black workers: Blind

alley occupations for workers who have latent capacity for other

jobs is, the rule rather than the exception among Negro workers. For

the Negro there is little encouragement and less opportunity for

promotion. Success stories of rises from laborer to superintendent

and manager are few. Opportunities for training are even more

restricted. Apprenticeships are few and other opportunities for

trade training rare. Schools do not see the wisdom of training Negro

pupils in skilled crafts because there is no opportunity for placing

them after they have been trained. Employers will not hire them

because they have no training. The vicious circle continues when a

privileged few do received the training or the required

apprenticeship only to find that white workers refuse to accept them

as fellow workmen. Strikes have been waged on this account. Union

workers have been known to walk off the jobs when a Negro fellow

unionist was employed. |

| As

the size of the black population in big cities grew, "Negro jobs"

became roughly institutionalized into an identifiable black sub-labor market

within the larger metropolitan labor market. The culture of control that was

embodied in the regulative systems which managed the black ghettos,

moreover, provided an effective, although less-rigid, variation of the Jim

Crow segregation that continued with hardly any change in the South.

Although the economic base of black tenancy was collapsing, its reciprocal

superstructure of political and social, controls remained the most-powerful

force shaping the place of blacks in society. The propertied and other

groups that had a vested interest in the special exploitation of the black

peasantry were still strong enough to maintain their hegemony over matters

concerning race. At the same time, the variation of Jim Crow that existed

in the North was more than simply a carry-over from the agrarian South.

These ghetto controls served the class function for industrial society of

politically and socially setting off that section of the proletariat that

was consigned to the least desirable employment. This racial walling off not

only was accomplished by direct ruling-class actions, but also was mediated

through an escalating reciprocal process in which the hostility and

competition of the white working class was stimulated by the growth of the

black proletariat and in return operated as an agent in shaping the new

racial controls. |

This

general pattern of restricting Black people to working-class jobs - and the

lowest level of these jobs at that - is known as the proletarianization of

Blacks.

Not

surprisingly, racial tension was quick to emerge in the urban areas, as

employers promoted competition for jobs and used Black workers as

strikebreakers against the white working class. "When the conflict

erupted into mass violence," Baron observes, "the dominant whites

sat back and resolved the crises in a manner that assured their continued

control over both groups."

During

the depression years, Black people were in dire economic straits in the

industrialized urban areas as millions were thrown out of work:

|

In

the first years of the slump, black unemployment rates ran about two- thirds

greater than white unemployment rates. As the depression wore on, |

But,

as Baron points out, "Two somewhat contradictory results stood out for

this period. First, whites were accorded racial preference as a greatly

disproportionate share of unemployment was placed on Black workers. Second,

despite erosion due to the unemployment differential, the black sub-sectors

of the urban labor markets remained intact." Thus, despite the fact

that Black people suffered disproportionately during the Great Depression,

they continued to adhere as a permanent part of the urban work force, albeit

at the lowest levels.

As the country geared up for World War II, initially "the black unemployed had to stand aside while the whites went to work." However, increased military mobilization finally swept Blacks back into the industrial work force:

|

The

vast demand for labor in general, that had to turn itself into a

demand for black labor, could only be accomplished by way of a great

expansion of the black sectors of metropolitan labor markets. Training

programs for upgrading to skilled and semiskilled jobs were opened up,

at first in the North and later in the South.... World War I had

established a space for black laborers as unskilled workers in heavy industry

. During World War II this space was enlarged to include a number of

semi-skilled and single-skilled jobs in many industries. World War II marked the most-dramatic improvement in economic status of black people that has ever taken place in the urban industrial economy. . , . Occupationally, blacks bettered their positions in all of the preferred occupations. The biggest improvement was brought about by the migration from South to North (a net migration of 1,600,000 blacks between 1940 and 1950). However within both sections the relative proportion of blacks within skilled and semi-skilled occupations grew. In clerical and lower-level professional work, labor shortages in the government bureaucracies created a necessity for a tremendous black upgrading into posts hitherto lily-white. |

Though

Blacks continued to face severe discrimination in employment following World

War II, the overall structure of the Black work force had been significantly

altered (see Chapter 7). During the first half of the 20th century, Black

men had been able to move from strictly unskilled labor positions into some

skilled labor jobs, mainly as operatives. Black women, particularly later

during the 1960s and 1970s, moved from domestic positions into service

positions.

On

the whole, the discrimination that Black people confronted in the northern

cities during the first half of the 20th century was less than that of the

rural experience, but in some respects it was greater. There was more

apparent social equality, the work paid more, and there was a great deal

more to do in the course of normal everyday life. However, life was cold and

impersonal, prices were higher, and there was much greater relative

deprivation. In the city a poor Black person was closer to wealth though

without it. It was easier to be without something in the South because Black

people there were quite distant from the general wealth of the middle and

ruling classes (except for the domestic servants, who were similar to the

house slaves), and because of the legacy of slavery.

.

The main process of life in the cities had to do

with the increased industrialization of Black workers. This process represented:

1. an increase in the skill level of Black workers;

2.

an increase in the pay of Black people, especially since both world wars

resulted in Black women getting factory jobs too, making a great deal more

money than they had ever made before (though it should be noted that Black

women were pushed out of their jobs immediately following both wars);

3.

an increased association with white workers on a more equal basis, resulting

in positive association in comparison with the more blatant racism and

oppression that had been the common experience in the South.

The

most important aspect of the urban experience for Black people was their

proletarianization.

CHANGES

IN SOCIAL AND CULTURAL LIFE

The

cultural life of Black people took a tremendous leap forward in the city,

both in quantity and quality. Immediately after the World War I migrations,

while the automobile and pre-depression prosperity of the U.S.A.

created the "roaring 20's," Black people in Harlem had a cultural

renaissance (rebirth). In every decade since, Black art and culture have

advanced in waves. (See Chapter 9, "Black Culture and the Arts.")

All of this has two tendencies: (1) more and more Black people have

assimilated the dominant culture, become proficient, and in some cases,

expert; and (2) the mass culture of Black people has changed to express the

urban working-class experience (rather than the rural tenant experience) and

has achieved a universal appeal that has continued to make a significant

impact on all U.S. culture and most peoples through- out the world.

In

the city Black people faced discrimination in housing so that segregated

Black neighborhoods were formed This approximated the rural experience in

the South so closely that in Chicago, for example, the South Side was called

Chicago's Black Belt. In 1919, Walter F. White observed:

|

Much

has been written and said concerning the housing situation in Chicago and

its effect on the racial situation. The problem is a simple one. Since

1915 the colored population of Chicago has more than doubled,

increasing in four years from a little over 50,000 to what is now

estimated to be between 125,000 and 150,000.... Already overcrowded

this so called "Black Belt" could not possibly hold the

doubled colored population. One cannot put ten gallons of water in

five-gallon pail. Although

many Negroes had been living in "white" neighborhoods, the

increased exodus from the old areas created an hysterical group of

persons who formed "Property Owners' Associations" for the

purpose of keeping intact white neighborhoods .... Early

in June the writer, while in Chicago, attended a private

meeting ... Various plans were discussed for

keeping the Negroes in "their part of the town," such as

securing the discharge of colored persons from positions they held

when they attempted to move into "white" neighborhoods,

purchasing mortgages of Negroes buying homes and ejecting them when

mortgage notes fell due and were unpaid and many more of the same caliber.

The language of many speakers was vicious and strongly prejudicial and

had the distinct effect of creating race bitterness. |

Writing in 1945, St. Clair Drake and Horace Cayton described what took place in Chicago in the intervening years:

|

The

Job Ceiling subordinates Negroes but does not segregate them.

Restrictive covenants do both. They confine Negroes to the Black Belt,

and they limit the Black Belt to the most rundown areas of the city.

There is a tendency, too, for the Negro communities to become the

dumping ground for vice, poor-quality merchandise, and inferior white

city officials. Housing is allowed to deteriorate and social services

are generally neglected. Unable to procure homes in other sections of

the city, Negroes congregate in the Black Belt... They

went on to analyze how segregated housing led to further social and

cultural segregation: The

conflict over living space is an ever-present source of potential

violence. It involves not only a struggle for houses, but also

competition for school and recreational facilities, and is further

complicated by the fact that Negroes of the lowest socioeconomic

levels are often in competition with middle class whites for an area.

Race prejudice becomes aggravated by class antagonisms, and

class-feeling is often expressed in racial terms. Residential segregation is not only supported by the attitudes of white people who object to Negro neighbors - it is also buttressed by the internal structure of the Negro community. Negro politicians and businessmen, preachers and civic leaders, all have a vested interest in maintaining a solid and homogeneous Negro community where their clientele is easily accessible. Black Metropolis, too, is an object of pride to Negroes of all social strata. It is their city within a city. It is something "of our own" It is concrete evidence. of one type of freedom - freedom to erect a community in their own image. Yet they remain ambivalent about residential segregation: they see a gain in political strength and group solidarity, but they resent being compelled to live in a Black Belt. |

Chicago's

Black Belt merely exemplified what was happening to Black people in urban

areas throughout the United States.

Based

on this geographical concentration, new ways were developed to oppress Black

people through city agencies organized on geographical lines. In the areas

of public education, police protection, parks and public recreational

facilities, water and sewage disposal, garbage collection, public health,

and public transportation, Black people were confronted with discrimination

that was not compensated for by the existence of a Black community. By

coming to the city, Black people did not escape oppression; they merely had

to face it in a new form.

RESISTANCE

Black

people fought against these new attacks against them. While geographic

concentration enabled the ruling class to orchestrate new forms of

oppression more effectively, it also enabled Black people to fight back with

more intensity, more force. Throughout their urban experience, Black people

have combined political pressure with such techniques as boycotts,

picketing, marches, demonstrations, and occasional violence to achieve their

ends.

Table 10 provides some examples of the means by which Black people in Chicago fought and the outcome of their struggles from 1929 to 1944.

Table

10

THE

STRUGGLE FOR JOBS IN CHICAGO

| Campaigns | Date | Groups Involved | Technique | Outcome |

| "Spend Your Money Where You Can Work" Campaign (directed at stores in the Black Belt) | 1929 | Sponsored by Negro Professionals -and Businessmen. (Led by white Race Radicals, with broad community support) | Boycott; picketing, |

Successful: 2,000 jobs in Black Belt stores |

| 51st Street Riot (directed at white laborers) | 1930 | Spontaneous outburst, by laborers | Violence | Successful |

| Fight for Skilled Jobs on Construction in Black Belt (directed at AFL building trades unions) | 1929 - 38 | Consolidated Trades Council - group of Negro artisans | Picketing; political pressure ; some violence | Partial success with advent of New Deal |

| Fight for Branch Managers with Daily Times | 1937 | Negro Labor Relations League - group of young men and women; some cooperation from Urban League and Politicians | Threat of boycott | Six managers appointed after one week campaign |

| Fight for Branch Managers, Evening American | 1937 | Negro Labor Relations League - group of young men and women; some cooperation from Urban League and politicians | Conference; implied threat of boycott | Eight managers appointed |

| Campaign for Motion Picture Operators in Black Belt (Directed against AFL Unions) | 1938 | Negro Labor Relations League - group of young men and women; some cooperation from Urban League and politicians | Picketing; threat of boycott | Ten operators appointed after short campaign |

| Campaign for Telephone Operators ( directed against phone company) | 1937 - 39 | Negro Labor Relations League - group of young men and women; some cooperation from Urban League and politicians | Treat that all Negros would remove telephones | Unsuccessful ; threat not carried out fully |

| Drive for Negro Milkmen (directed against major dairies and AFL unions ) | 1929 - 39 | Fight begun by Whip; revived in 1937 by Council of Negro Organizations and Negro Labor Relations League | Threat of boycott; attempt to organize "Milkless Sunday" | Unsuccessful due to lack of community support |

| Campaign for bus drivers and motormen on transit lines | 1930 - 44 | "United front with strong leftwing influence; campaign aided by FEPC | Demonstrations; threat of boycott; strong political pressure | Successful in securing a few positions |

Source: St. Clair Drake and Horace R- Cayton, Black Metropolis, p. 743.

Elsewhere Blacks also took up militant means. The 1935 riot that

broke out in Harlem marked "the first time blacks moved ion and

employed violence on a retaliatory basis against white storeowners," as

Baron observed. It was a technique

that was to be used in later years. Another one of the ways to struggle was

based on the concentration of buying power. Black people used their money to

force merchants to hire Black people by shopping only where Black people

worked. During the 1920s, Black bourgeois leaders organized "Don't Buy

Where You Can't Work" campaigns to gain jobs in white firms operating

in the ghettos. Later, the Doctrine of the Double-Duty Dollar was preached,

often from the pulpit. St' Clair Drake and Horace Cayton described -in

1945 the meaning of this doctrine and its importance to the Black community:

|

It

is Sunday morning in the "black belt

" The pastor of one of the largest churches has just

finished his morning prayer. There is an air of quiet expectancy, and

then - a most unusual discourse begins. The minister, in the homely,

humorous style so often affected by Bronzeville's "educated"

leaders when dealing with a mass audience, is describing a business

exposition: "The

Business Exposition at the Armory was one of the finest achievements

of our people in the history of Chicago. Are there any members of the

Exposition Committee here? If so, please stand. [A man stands.] Come

right down here where you belong; we've got a seat right here in front

for you. This man is manager of the Apex Shoe Store - the shoes that I

wear.. We can get anything we want to wear or eat from Negroes today.

If you would do that it would not only purchase the necessities of

life for you, but would open positions for your young folks. You can

strut as much as you want to and look like Miss Lizze [an upper-class

white person], but you don't know race respect if you don't buy from

Negroes. As soon as these white folks get rich on the South Side, they

go and live on the Gold Coast, and the only way you can get in is by

washing their cuspidors. Why not go to Jackson's store, even if you

don't want to buy nothing but a gingersnap?

Do that and encourage those girls working in there. Go in

there and come out eating. Why don't you do that?" This

is the doctrine of the "Double-Duty Dollar," preached from

many Bronzeville pulpits as a part of the weekly ritual. Church

newspapers, too, carry advertisements of all types of business from

"chicken shacks" to corset shops. Specific businessmen are

often pointed out to the congregations as being worthy of emulation

and support, and occasional mass meetings stress the virtues of buying

from Negroes - of making the dollar do "double-duty": by

both purchasing a commodity and "advancing The Race." The

pastor quoted above had been even more explicit in an address before

the Business Exposition crowd itself: "Tomorrow

I want all of YOU people to go to these stores. Have your shoes

repaired at a Negro shop, buy your groceries from a Negro grocer ...

and for God's sake, buy your meats, pork chops, and yes, even your

chitterlings, from a Negro butcher. On behalf of the Negro

ministers of Chicago I wish to commend these Negro businessmen for

promoting such an affair, and urge upon you again to patronize your

own, for that is the only way we as a race will ever get

anywhere."' . . . This

endorsement of business by the church simply dramatizes,

and brings the force of sacred, sanctions to bear upon, slogans

that the press, the civic organizations,

and even the social clubs repeat incessantly, emphasizing the duty of

Negroes to trade with Negroes and promising ultimate racial "salvation"

if they will support racial business enterprises.... To

the Negro community, a business is more than a mere enterprise to make

profit for the owner. From the standpoints of both the customer and

the owner it becomes a symbol of racial progress, for better or for

worse. |

In

addition to these consumer boycotts, mass protests were organized in many

different ways. For instance, in January of 1941, A. Philip Randolph,

president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, an all-Black union,

called for a massive march on Washington. The March on Washington Movement

received sufficient support to force President Roosevelt to establish a Fair

Employment Practice Committee in exchange for calling off the march.

"Although this movement was not able to establish a firmly-organized

class base or sustain itself for long,"

Harold Baron maintains, "it foreshadowed a new stage of development

for a self-conscious working class with the appeal that an oppressed people

must accept the responsibility and take the initiative to free

themselves."

The March on Washington Movement triggered off a long history of marches on

Washington that continue to this day.

Lastly,

and most importantly, since Black people were becoming workers, the fight

against discrimination was aimed at racist practices by both industry and

segregated unions. This took its most advanced form in the 1930s with the

development of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (the CIO) and

campaigns in such basic industries as steel and automobile production. In

the next chapter, we will take up in more detail the experiences of Black

people as industrial workers in urban centers.

KEY CONCEPTS

| Consumer boycott | "New" Negro | |

| Double Duty Dollar | Push/Pull | |

| Ghetto | Proletarianization | |

| Migration | Urban Black Belt | |

| "Negro jobs"/Job ceiling | Urbanization/Suburbanization |

STUDY

QUESTIONS

I.

Why did Black people migrate to the cities, particularly the northern

industrial cities? How was the agricultural experience of Black people

similar to and different from the industrial experience?

2.

What kinds of jobs did Black people get in the city?

3.

What were the major forms of discrimination and oppression experienced by

Black people in the city?

4.

How did Black people fight back during this period?

SUPPLEMENTARY

READINGS

1. Constance McLaughlin Green, The Secret City: A History of Race Relations in the Nation's Capital. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967.

2. Theodore Kornweibel, Jr., In Search of the Promised Land: Essays in Black Urban History. Port Washington: Kennikat Press, 1981.

3. Hollis R. Lynch, The Black Urban Condition: A Documentary History, 1866-1971. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1973.,

4.

Gilbert Osofsky, Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto. New York: Harper and

Row, 1966.

5, Allen H. Spear, Black Chicago: The Making of a Negro Ghetto 1890-1920. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967.